July 10, 2008

Senate Backs Wiretap Bill to Shield Phone Companies

WASHINGTON — More than two and a half years after the disclosure of President’s Bush’s domestic eavesdropping program set off a furious national debate, the Senate gave final approval on Wednesday afternoon to broadening the government’s spy powers and providing legal immunity for the phone companies that took part in the wiretapping program.

The plan, approved by a vote of 69 to 28, marked one of Mr. Bush’s most hard-won legislative victories in a Democratic-led Congress where he has had little success of late. Both houses, controlled by Democrats, approved what amounted to the biggest restructuring of federal surveillance law in 30 years, giving the government more latitude to eavesdrop on targets abroad and at home who are suspected of links to terrorism.

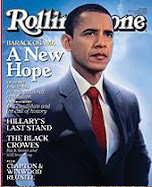

The issue put Senator Barack Obama of Illinois, the presumptive Democratic nominee, in a particularly precarious spot. After long opposing the idea of immunity for the phone companies in the wiretapping operation, he voted for the plan on Wednesday. His reversal last month angered many of his most ardent supporters, who organized an unsuccessful drive to get him to reverse his position once again. And it came to symbolize what civil liberties advocates saw as “capitulation” by Democratic leaders to political pressure from the White House in an election year.

Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton of New York, who was Mr. Obama’s rival for the Democratic presidential nomination, voted against the bill.

The outcome was a stinging defeat for opponents who had urged Democratic leaders to stand firm against the White House after a months-long impasse.

“I urge my colleagues to stand up for the rule of law and defeat this bill,” Senator Russell D. Feingold, Democrat of Wisconsin, said in closing arguments.

But Senator Christopher S. Bond, the Missouri Republican who is vice chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, said there was nothing to fear in the bill “unless you have Al Qaeda on your speed dial.”

Supporters of the plan, which revised the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, said that the final vote reflected both political reality and legal practicality. Wiretapping orders approved by a secret court under the previous version of the surveillance law were set to begin expiring in August unless Congress acted, and many Democrats were wary of going into their political convention in Denver next month with the issue hanging over them—handing the Republicans a potent political weapon.

Voting for the bill were 47 Republicans, 21 Democrats and an independent, Senator Joseph I. Lieberman of Connecticut. Twenty-seven Democrats and Senator Bernard Sanders, independent of Vermont, voted against it. Not voting were Senators; John McCain of Arizona, campaigning for the Republican presidential nomination, and Jeff Sessions, Republican of Alabama, both of whom would have been expected to voted “yes” Senator Edward M. Kennedy, Democrat of Massachusetts, who was a sharp critic of the bill, was not present for the vote, but later returned to the floor to applause after being sidelined with cancer.

The surveillance plan, which Mr. Bush is expected to sign into law quickly, was the product of months of negotiations between the White House and Democratic and Republican leaders, earning the grudging support of some leading Democrats.

Senator John D. Rockefeller IV, the West Virginia Democrat who leads the intelligence committee and helped broker the deal, said modernizing the 1978 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act was essential to protecting national security and giving intelligence officials the technology tools they need to deter another terrorist strike. But he said the plan “was made even more complicated by the president’s decision, in the aftermath of September 11, 2001, to go outside of F.I.S.A. rather than work with Congress to fix it.”

He was referring to the secret program approved by Mr. Bush weeks after the Sept. 11 that allowed the National Security Agency, in a sharp legal and operational shift, to wiretap the international communications of Americans suspected of links to Al Qaeda without first getting court orders. Disclosure of the program in December 2005 by The New York Times led to lawsuits and condemnation from critics, including one federal judge who ruled that the program was illegal, only to be overruled on appeal. It also set off many rounds of abortive attempts in Congress to find a legislative solution.

The key stumbling block in the congressional negotiations was the insistence by the White House that any legislation include legal immunity for the phone companies that took part in the wiretapping program. The program itself ended in January 2007, when the White House agreed to bring it under the auspices of the special court set up by the earlier surveillance law, known as the F.I.S.A. court. Still, more than 40 lawsuits continued churning through federal courts, charging AT&T, Verizon and other major carriers with breaking the law and violating their customers’ privacy by agreeing to the White House’s requests to conduct wiretaps without a valid court order.

The deal approved on Wednesday, which passed the House on June 20, effectively ends those lawsuits. It includes a narrow review by a district court to determine whether in fact the companies being sued received formal requests or directives from the administration to take part in the program. The administration has already acknowledged that those directives exist. Once such a finding is made, the lawsuits “shall be promptly dismissed,” the bill says. Republican leaders say they regard the process as a formality in ensuring that the phone carriers are protected from any legal liability over their participation.

Liberal Democrats in the Senate, led by Senators Feingold and Christopher J. Dodd of Connecticut, sought in vain to pare down the proposal. An amendment sponsored by Mr. Dodd to strip the immunity provision from the bill was defeated, 66 to 32.

Two other amendments were also rejected. One, offered by Senator Arlen Specter, Republican of Pennsylvania, would have required that a district court judge assess the legality of warrantless wiretapping before granting immunity. It lost by 61 to 37. The other, which would have postponed immunity for a year pending a federal investigation, was offered by Senator Jeff Bingaman, Democrat of New Mexico. It was defeated by 56 to 42.

Lawyers involved in the lawsuits against the phone companies promised to challenge the immunity provision in federal court, although their prospects appeared dim.

“The law itself is a massive intrusion into the due process rights of all of the phone subscribers who would be a part of the suit,” said Bruce Afran, a New Jersey lawyer who represents several hundred plaintiffs in one lawsuit against Verizon and other companies. “It is a violation of the separation of powers. It’s presidential election-year cowardice. The Democrats are afraid of looking weak on national security.”

The legislation also expands the government’s power to invoke emergency wiretapping procedures. While the National Security Agency would be allowed to seek court orders for broad groups of foreign targets, the law creates a new, 7-day period for targeting foreigners without a court order in “exigent” circumstances if government officials assert that important national security information would be lost otherwise. The law also expands from three to seven days the period in which the government can conduct emergency wiretaps without a court on Americans if the attorney general certifies that there is probable cause to believe the target is linked to terrorism.

Democrats pointed to some concessions they had won from the White House in the lengthy negotiations. The final bill includes a reaffirmation that the surveillance law is the “exclusive” means of conducting intelligence wiretaps — a provision that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and other Democrats insisted would prevent Mr. Bush or any future president from evading court scrutiny in the way that the N.S.A. program did.

The measure will also require reviews by the inspectors general from several agencies to determine how the program was operated. Democrats said that the reviews should provide accountability that had been missing from the debate over the wiretaps.

David Stout contributed reporting.

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/10/washington/10fisa.html

No comments:

Post a Comment