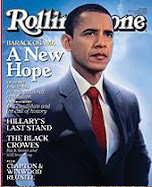

| Barack Obama is a really unique personality. He is very complex. Yet, he is a star. McCain says he is a celebrity. McCain was fifth from the bottom of his class at Annapolis. Barack Obama was president of the Harvard Law Review. We can only assume that the celebrity charge is a cover-up for McCain’s inadequacy. Barack draws 200,000 people in Berlin. McCain shows up to a crowd of 50,000 Harleys. The Rovian tactic is attack the opponent’s strength. All of that aside, this article by Jodi Kantor (Jeremiah Wright accused Jodi Kantor of misrepresenting his ideas) shows aspects of Barack that are unseen. RGN |

August 28, 2008

Man in the News

For a New Political Age, a Self-Made Man

By JODI KANTOR

DENVER — From the earliest days of his presidential campaign, those around Senator Barack Obama have heard the same mantra. He repeated it after he announced his candidacy and after debates, after victories and defeats.

“I need to get better,” he would say.

In the way Mr. Obama has trained himself for competition, he can sometimes seem as much athlete as politician. Even before he entered public life, he began honing not only his political skills, but also his mental and emotional ones. He developed a self-discipline so complete, friends and aides say, that he has established dominion over not only what he does but also how he feels. He does not easily exult, despair or anger: to do so would be an indulgence, a distraction from his goals. Instead, they say, he separates himself from the moment and assesses.

“He doesn’t inhale,” said David Axelrod, his chief strategist.

But with Barack Hussein Obama officially becoming the Democratic presidential nominee on Wednesday night, some of the same qualities that have brought him just one election away from the White House — his virtuosity, his seriousness, his ability to inspire, his seeming immunity from the strains that afflict others — may be among his biggest obstacles to getting there.

There is little about him that feels spontaneous or unpolished, and even after two books, thousands of campaign events and countless hours on television, many Americans say they do not feel they know him. The accusations of elusiveness puzzle those closest to the candidate. Far more than most politicians, they say, he is the same in public as he is in private.

The mystery and the consistency may share the same root: Mr. Obama, 47, is the first presidential candidate to come of age during an era of relentless 24-hour scrutiny. “He is, more than any other contemporary political figure, a creature of these times,” said Representative Earl Blumenauer, a fellow Democrat who campaigned this spring with Mr. Obama in Oregon, Mr. Blumenauer’s home state.

Last month, while visiting Jerusalem, Mr. Obama crammed a note in the Western Wall that was promptly fished out and posted on the Internet. The message was elegantly phrased, as if Mr. Obama, a Christian, had anticipated that his private words to the Almighty would soon be on public display.

In the note, Mr. Obama asked for protection, forgiveness and wisdom, a message in keeping with the humility he tries to emphasize. But his uncanny self-assurance and seemingly smooth glide upward have stoked complaints from his critics and his opponents, first Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton and now Senator John McCain, that he has not spent enough time earning and learning, that his main project in life has been his own ascent.

Because he betrays little hint of struggle, Mr. Obama can seem far removed from the troubles of some voters. Older working-class whites may be uncomfortable with his race — he is the son of a white mother from Kansas and a black father from Kenya — and his age. But they may also find it hard to identify with him, even though he tries to assure them that they have much in common, mentioning that his mother relied on food stamps at times and that he worked as a community organizer in Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods. His command of crowds of 75,000, his unfailing eloquence and his comparing himself to Joshua and Lincoln can belie his point.

These voters are not the first to see a contradiction between Mr. Obama’s aura of specialness and his insistence that he is just like everyone else.

“I’m just a first among equal folks,” Mr. Obama’s fellow editors at the Harvard Law Review wrote about him in an affectionate but biting parody issue after he was elected its president. “But still, no one’s interviewing any of them.”

Racing to the Top

Nearly a decade ago, Mr. Obama joined luminaries like George Stephanopoulos and Ralph Reed for regular seminars, organized by Robert Putnam, a professor at Harvard and the author of “Bowling Alone,” about the deterioration of American community ties. As a young state senator from Illinois, Mr. Obama was one of the less prominent members of the group. But soon everyone was referring to him as “the governor” — a friendly smack, said Mr. Putnam, at Mr. Obama’s precocity and drive.

From an early age, Mr. Obama was taught by his mother to think grandly about his potential to help others. Once he reached adulthood, admiring teachers and mentors reinforced the message, steadily directing his sights higher and higher. As a law student, he mused about wanting to be mayor of Chicago; as a law professor, he talked about running for governor of Illinois; not long after that, he was running for president.

Mr. Obama groomed himself more carefully than he sometimes admits. In an interview this year, he denied that he wrote “Dreams From My Father,” the post-law-school memoir that has enchanted so many followers, with political ambitions in mind. But his Harvard law school classmates say Mr. Obama was already talking about a future run for public office. To truly address the poverty and injustice he had seen as an organizer, he would need to gain some power.

Starting in law school, Mr. Obama began pulling together a large cast of mentors, well-connected and civic-minded friends who rose in Chicago and Illinois politics along with him, including a spouse he thought was ideal.

“He loved Michelle,” said Gerald Kellman, Mr. Obama’s community organizing boss, but he was also looking for the kind of partner who could join him in his endeavors. “This is a person who could help him manage the pressures of the life he thought he wanted.”

Mr. Obama won his army of powerful champions — including Abner J. Mikva, a former federal judge; Tom Daschle, a former Senate majority leader; Senator Edward M. Kennedy; and too many Chicago leaders to count — by impressing them with his intellectual heft and idealism, but also with his eagerness to absorb their lessons. As a man who barely knew his own father, Mr. Obama might have sought many things from these figures: authority, security, even love.

But his needs were more concrete, Mr. Kellman said. “He forms mentorships in order to learn,” he said. “He wants to know what they know.”

Both allies and critics sometimes concluded that Mr. Obama was too gifted, or in too much of a hurry, for the tasks that consumed others.

“I thought of him much more as a colleague” than a student, said Laurence Tribe, a law professor at Harvard for whom Mr. Obama worked. “I didn’t think of him as someone to send out on mechanical tasks of digging out all the cases.” Other students could do that, Professor Tribe added.

Mr. Obama’s campaign promotes accomplishments from his days in the Illinois Senate: He successfully championed campaign finance and racial profiling laws, as well as child care subsidies and tax credits for the working poor. But “he didn’t participate in rank-and-file things,” said John Corrigan, a former consultant to the State Senate’s Democratic caucus. “He was destined for something bigger than potholes.”

And in the United States Senate, Mr. Obama leads a subcommittee on European affairs, but he has not held any oversight hearings to investigate foreign policy issues, just a few to discuss nominations.

The McCain campaign has seized on this pattern, mocking its opponent as a self-consumed star, even suggesting that he has a messianic complex.

Mr. Obama has heard the accusations before. Long before the presidential race, some around him seemed to resent his ability to galvanize a following. “Bluebooking is not important for celebrities,” fellow students joked about him in the law review parody, referring to the tedious process of checking citations.

As for the messiah accusation, Michael Madigan, the speaker of the Illinois House of Representatives and a Democrat, once publicly called Mr. Obama the same thing.

Disciplined and Detached

If there is one quality that those closest to Mr. Obama marvel at, it is his emotional control. This is partly a matter of temperament, they say, partly an effort by Mr. Obama to step away from his own feelings so he can make dispassionate judgments. “He doesn’t allow himself the luxury of any distraction,” said Valerie Jarrett, a close adviser. “He is able to use his disciplined mind to not get caught up in the emotional swirl.”

In 2006, Mr. Obama backed Alexi Giannoulias, a 29-year-old friend from the basketball court, for Illinois treasurer. Opponents accused Mr. Giannoulias of corruption, citing thin evidence: a loan his family’s bank made to a convicted felon. After Mr. Giannoulias worsened the situation by calling the felon a nice guy, Mr. Obama told him to fix his campaign or get out of the race.

“I was almost crying,” said Mr. Giannoulias, who eventually won. “He was almost upset at how thin-skinned I was.”

It is not that Mr. Obama does not experience emotion, friends say. But he detaches and observes, revealing more in his books than he does in the moment. “He has the qualities of a writer,” Mr. Axelrod said. “I get the sense that he’s participating in these things but also watching them.”

Mr. Obama watches no one more avidly than himself. During the primary season, supporters who complimented him on debate appearances found that he often disagreed. “I wasn’t great nor was I wonderful,” Mr. Obama responded last spring at a fund-raiser in Seattle. Then came his usual refrain: “I have to get better, and I will do better,” he said, according to Michael Parham, a donor.

As a campaigner, Mr. Obama had to learn to sometimes let simple emotion rule. When Mr. Axelrod first devised “Yes We Can” as a slogan during Mr. Obama’s Senate campaign, the candidate resisted: it was a little corny for his taste. “That’s where the high-minded and big-thinking Barack came in,” said Peter Giangreco, a consultant to the Obama campaign. “His initial instincts were off from where regular people’s were.”

While he speeds along rope lines, Mr. Obama sometimes connects better one on one. In spare moments, he will surprise supporters — a doorman who scraped together a small contribution, an elderly woman he had heard enjoyed his memoir — with an out-of-the blue phone call. Waiting backstage to speak to 20,000 people in Seattle in February, Mr. Obama grew so absorbed in talking to a retired Michigan couple that he had to be reminded not to miss his entrance cue.

Once in a very long while, Mr. Obama will relax his guard completely. Two years ago at a party celebrating the publication of his second book, “The Audacity of Hope,” the new senator rose to say a few words, recalled Ms. Jarrett. As he talked about what his new job in Washington had cost his wife and two daughters, tears began to course down his face, leaving him unable to continue.

Michelle Obama rescued him with a kiss, and after a moment, everyone started to applaud.

An Outsider’s New Role

Mr. Obama is often called a perpetual outsider — racially, geographically, politically. But his story is more complicated than that. “He’s been an outsider at Columbia and Harvard,” said Matthew McGuire, a friend. “He was an outsider but within the ultimate insider clubs.”

Within those and other powerful institutions, Mr. Obama has always appointed himself critic. After being elected the first African-American president of the Harvard Law Review, Mr. Obama gave a speech to black students and alumni that was rousing, some recall it nearly two decades later. “Don’t let Harvard change you,” went the refrain. As a community organizer, he led Chicago residents to challenge the local authorities. In the Illinois Senate, Mr. Obama was not only a reformer who pushed for tighter campaign finance rules, but also an everyday skeptic who often pointed out hilarities and hypocrisies to colleagues.

Despite the speed of his rise, Mr. Obama often talks of politics as a closed system, one stacked against outsiders who lack powerful patrons or fat donor bases.

These sorts of criticisms have become the cornerstone of his political identity. Changing government, making it more responsive to citizens’ needs, has been the promise of every campaign he has ever run. Today, despite the millions of people and dollars devoted to his election, Mr. Obama insists, improbably enough, that he is still the same advocate for the poor he was 20 years ago on the streets of Chicago.

“All the time, he says, let’s keep in mind that this is not about Barack Obama,” said Ms. Jarrett, an adviser. “He still sees himself as the community organizer.”

But after he accepts his party’s nomination on Thursday night, it will be hard to call Mr. Obama anything but the establishment. As head of his party, he will preside over everything he says he objects to about politics: the artifice, the influence of special interests, the partisanship. If he wins the presidency, there will be no more rungs on the ladder for Mr. Obama to climb, only re-election. The system he says is broken will become his.

Even those closest to him are not quite sure how he would make the transformation.

“That’s uncomfortable,” said Mr. Axelrod, about the prospect of Mr. Obama’s becoming the ultimate insider. “You need to accept that role to a degree if you’re the nominee or the president.”

And yet, Mr. Axelrod said, “I don’t think that’s a role he wants to play. His idea is that you should always be challenging the institution.”

No comments:

Post a Comment