Friday, March 19, 2010

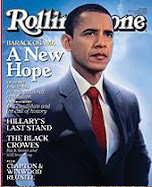

"Progressive Pragmatism": Is Obama a President of Consequence

The most interesting thing about this piece by Ron Brownstein is that it is reminiscent of an old saying: don't mistake kindness for weakness. According to Brownstein, on the issue of health care, Obama took the risk of doing really big and really risky, stood steadfast on achieving an accomplishment of historic proportions. Essentially, even though Brownstein does not say it exactly, with the passage of health care Obama will have been a consequential president. He will have gotten passed into law legislation a social policy no less important than the 1964 Civil Rights Act, or Medicare, or social security. That is the stuff upon which the terms greatness or at least significant presidencies are born. Brownstein argues, without saying so, that Obama really is a "progressive pragmatist," who is showing strength and determination in his major mission is to “transform America.” RGN

POLITICAL CONNECTIONS

Obama And The Supertanker

The constant in Obama's presidency has been his determination to chart a new course.

by Ronald Brownstein

Saturday, March 20, 2010

At various points in health care reform's long slog through Congress, White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel has offered President Obama options to settle for more-incremental change. But at each juncture, Obama has persisted in pursuing a

comprehensive, big-bang bill.

In an interview with National Journal, Emanuel said he has intermittently provided Obama his assessment of "the equities" in more- and less-ambitious approaches, especially "given everything [else] we're trying to do." He continued, "This is what I'm supposed to do as chief of staff. But he has... always said, 'This is what needs to be done,' and he has said he is willing to pay the political price to get it done."

The grueling health care struggle, now nearing a decisive vote in the House, has filled in a picture of Obama that remained stubbornly unfinished through his first year. Most immediately, it has shattered the image of him as a passionless president, too cool to fully commit to any cause.

Win or lose, Obama has pursued health care reform as tenaciously as any president has pursued any domestic initiative in decades. Health care has now been his presidency's central domestic focus for a full year. That's about as long as it took to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, originally introduced by John F. Kennedy and driven home by Lyndon Johnson. Rarely since World War II has a president devoted so much time, at so much political cost, to shouldering a single priority through Congress. It's reasonable to debate whether Obama should have invested so heavily in health care. But it's difficult to quibble with Emanuel's assessment that once the president placed that bet, "He has shown fortitude, stamina, and strength."

The fight has opened a second window into Obama. The key here is his 2008 campaign assertion that "Ronald Reagan changed the trajectory of America" more than Richard Nixon or Bill Clinton did. The health care struggle suggests that Obama views changing that trajectory as the ultimate measure of a presidency's success. His aim is to establish a long-term political direction -- one centered on a more activist government that shapes and polices the market to strengthen the foundation for

aim is to establish a long-term political direction -- one centered on a more activist government that shapes and polices the market to strengthen the foundation for sustainable, broadly shared growth. Everything else -- the legislative tactics, even most individual policies -- is negotiable. He wants to chart the course for the supertanker, not to steer it around each wave or decide which crates are loaded into its hull.

Obama's core health care goals have been to establish the principle that Americans are entitled to insurance and to build a framework for controlling costs by incentivizing providers to work more efficiently. He has been unwavering about that destination but flexible and eclectic in his route. He has cut deals with traditional adversaries, such as the drug industry, and confronted allies to demand an independent Medicare reform commission. But Obama has also waged unconditional war on the insurance industry. He has negotiated and jousted with Senate Republicans. He has deferred (excessively at times) to congressional Democratic leaders but has also muscled them at key moments. He has pursued the liberal priority of expanded coverage through a centrist plan that largely tracks the Republican alternative to Clinton's 1993 proposal.

Yale University political scientist Stephen Skowronek, a shrewd student of the presidency, sees in this complex record evidence that Obama and his team are torn between consensual and confrontational leadership styles. The first, he says, stresses "the progressive reform idea of bringing everybody to the table [for] rational, pragmatic decision-making." The second argues "that you transform politics only through wrenching confrontation." Skowronek believes that the most-consequential presidents, such as Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt, usually start with the first approach and evolve toward the second as they encounter entrenched resistance.

Liberals who consider Obama too conciliatory have speculated that his willingness to use the Senate reconciliation process to force a final vote on health care signals a turn toward consistent confrontation. But it seems more likely that he will continue to seek broad coalitions on some issues (education, energy, immigration) while accepting, even welcoming, greater partisan conflict on others (financial reform).

The approaches that Skowronek views as alternatives Obama may consider tools he can wield in different combinations for each challenge. The constant is Obama's determination to turn the supertanker -- and his Reagan-like willingness to bet his party's future on his ability to sell the country on the ambitious course he has set.

POLITICAL CONNECTIONS

Obama And The Supertanker

The constant in Obama's presidency has been his determination to chart a new course.

by Ronald Brownstein

Saturday, March 20, 2010

At various points in health care reform's long slog through Congress, White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel has offered President Obama options to settle for more-incremental change. But at each juncture, Obama has persisted in pursuing a

comprehensive, big-bang bill.

In an interview with National Journal, Emanuel said he has intermittently provided Obama his assessment of "the equities" in more- and less-ambitious approaches, especially "given everything [else] we're trying to do." He continued, "This is what I'm supposed to do as chief of staff. But he has... always said, 'This is what needs to be done,' and he has said he is willing to pay the political price to get it done."

The grueling health care struggle, now nearing a decisive vote in the House, has filled in a picture of Obama that remained stubbornly unfinished through his first year. Most immediately, it has shattered the image of him as a passionless president, too cool to fully commit to any cause.

Win or lose, Obama has pursued health care reform as tenaciously as any president has pursued any domestic initiative in decades. Health care has now been his presidency's central domestic focus for a full year. That's about as long as it took to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, originally introduced by John F. Kennedy and driven home by Lyndon Johnson. Rarely since World War II has a president devoted so much time, at so much political cost, to shouldering a single priority through Congress. It's reasonable to debate whether Obama should have invested so heavily in health care. But it's difficult to quibble with Emanuel's assessment that once the president placed that bet, "He has shown fortitude, stamina, and strength."

The fight has opened a second window into Obama. The key here is his 2008 campaign assertion that "Ronald Reagan changed the trajectory of America" more than Richard Nixon or Bill Clinton did. The health care struggle suggests that Obama views changing that trajectory as the ultimate measure of a presidency's success. His aim is to establish a long-term political direction -- one centered on a more activist government that shapes and polices the market to strengthen the foundation for

aim is to establish a long-term political direction -- one centered on a more activist government that shapes and polices the market to strengthen the foundation for sustainable, broadly shared growth. Everything else -- the legislative tactics, even most individual policies -- is negotiable. He wants to chart the course for the supertanker, not to steer it around each wave or decide which crates are loaded into its hull.

Obama's core health care goals have been to establish the principle that Americans are entitled to insurance and to build a framework for controlling costs by incentivizing providers to work more efficiently. He has been unwavering about that destination but flexible and eclectic in his route. He has cut deals with traditional adversaries, such as the drug industry, and confronted allies to demand an independent Medicare reform commission. But Obama has also waged unconditional war on the insurance industry. He has negotiated and jousted with Senate Republicans. He has deferred (excessively at times) to congressional Democratic leaders but has also muscled them at key moments. He has pursued the liberal priority of expanded coverage through a centrist plan that largely tracks the Republican alternative to Clinton's 1993 proposal.

Yale University political scientist Stephen Skowronek, a shrewd student of the presidency, sees in this complex record evidence that Obama and his team are torn between consensual and confrontational leadership styles. The first, he says, stresses "the progressive reform idea of bringing everybody to the table [for] rational, pragmatic decision-making." The second argues "that you transform politics only through wrenching confrontation." Skowronek believes that the most-consequential presidents, such as Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt, usually start with the first approach and evolve toward the second as they encounter entrenched resistance.

Liberals who consider Obama too conciliatory have speculated that his willingness to use the Senate reconciliation process to force a final vote on health care signals a turn toward consistent confrontation. But it seems more likely that he will continue to seek broad coalitions on some issues (education, energy, immigration) while accepting, even welcoming, greater partisan conflict on others (financial reform).

The approaches that Skowronek views as alternatives Obama may consider tools he can wield in different combinations for each challenge. The constant is Obama's determination to turn the supertanker -- and his Reagan-like willingness to bet his party's future on his ability to sell the country on the ambitious course he has set.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment