Thursday, March 18, 2010

Time to Abandon Bi-Partisanship: Time to say No to the Part of No!!

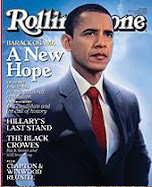

Kutter thinks that Obama has learned an important lesson when it comes to the Republicans: time to forget bi-partisanship. It is obvious that the Republicans are the "party of no." This an excellent analysis on Obama's development as President. Obama's style is reconcile differences in a non-ideological fashion. It seems as though the lesson to abandon "reaching out" to Republicans is a failed strategy and Obama's style the last few weeks in which he is taking on the Republicans is a reflection of lessons learned. Check out Kutter. RGN

The End of an Illusion

Robert Kuttner

Co-Founder and Co-Editor of The American

Prospect

March 14, 2010 10:30 PM

Are we at a turning point in the Obama presidency? It

took far too long, but the president has belatedly

grasped that when the other party is out to destroy you,

the search for common ground is a fool's errand.

For over a year, Obama believed that reform required him

to govern as a post-ideological bipartisan. Now,

mercifully, he has learned that progressive leadership

demands taking on the Republicans, just as it requires

taking on the insurance and banking industries. There is

little common ground on those fronts either.

Since early March, Obama has begun to sound more like

the bold figure who won the hearts of voters during the

campaign. The showdown is expected late next week.

Speaker Nancy Pelosi seldom schedules a vote without

having a majority in her pocket. With all the bill's

deficiencies, winning its passage would be a triumph,

not just for expansion of health coverage, but for

Obama's capacity to learn and grow in office and defeat

Republican obstruction.

Should he succeed, there will be little public sympathy

for Republican caviling about the use of the

reconciliation progress to, well, reconcile differences

between the House and Senate bills. Technical

parliamentary complaints will seem more like the

bleating of sore losers. Obama can seize the high ground

of majority rule.

And thanks to the sheer extremism of episodes like Sen.

Jim Bunning's attempted blockage of unemployment

insurance, Liz Cheney's association of lawyers honoring

the constitutional right to legal counsel with treason;

and the refusal of Congressional Republicans to back

even token recovery spending, Obama is well positioned

to define a new political mainstream even as he becomes

a more effective partisan progressive.

This odyssey was not an easy journey, and it is far from

complete. Obama's belief in common ground runs very deep

in his being. It remains to be seen whether his

reluctant embrace of partisanship to win the health

reform battle marks a durable change in his governing

style, or a one-off. But a victory on this defining

issue, after months of defeatism, would surely taste

sweet and would very likely mark a shift in Obama's

conception of leadership.

I say all this despite serious misgivings about the

health plan itself. The compulsory mandate is a

fundamental flaw, as Obama himself recognized during the

campaign. There is a world of difference between true

social insurance and a mandate to purchase a private

product. The former reinforces the value of government

and of social solidarity; the latter signals a coercive

state in concert with private industry profits. The

proposed tax on decent insurance was a tone-deaf assault

on wage earners for whom good health coverage is a rare,

reliable island in a rising sea of economic insecurity.

The diversion of Medicare funds was a political gift to

Republicans. And the back-loading of benefits purely for

budgetary reasons made the bill a political piñata, with

the risks evident and the gains deferred.

All of these elements made the plan a harder sell with

legislators of Obama's own party -- but all can be

fixed. At the end of the day, even Congressional

Democrats who worried that voters might punish them for

supporting this measure grasped a more fundamental

political truth: winning beats losing. There will be

time to improve the bill, particularly now that

Democrats have given themselves permission to use

majority rule rather than defer to Republican

obstruction.

Obama's new stance also serves as a role model. Senate

Banking Chairman Chris Dodd's belated abandonment of a

futile bipartisan approach to financial reform provides

a bookend to the president's new partisan leadership on

health reform.

Obama has also just appointed three relative

progressives to the Federal Reserve, including Sarah

Bloom Raskin of Maryland, widely considered the best of

the state financial regulators. There is not a single

businessman or banker in the lot.

Including in the health package an overhaul of the

student loan program, long blocked in the senate, is

another welcome demonstration of presidential nerve. But

prevailing on this first round of health reform will be

just the first step on a long road back.

Though both Obama and the Republicans treated health

reform as the defining issue of his presidency, other

challenges loom far larger. Obama has to do better on

employment, mortgage relief, and financial reform. He

has to deliver more tangible help to people for whom

this recovery still feels like a depression.

Presidential leadership has been crowded out by the

grand distraction of health reform and by Obama's own

reluctance to think bigger and fight harder. In these

critical areas too, corporate and partisan adversaries

have blocked progress. For this to be a true turning

point, his new-found partisanship and bolder progressive

stance must extend to the larger enterprise of restoring

prosperity.

If Obama wins health reform, and goes on to fight harder

for a real recovery program, some future historian

(doubtless guided by extended interviews with Rahm

Emanuel) will report that this latest turn to aggressive

partisanship was all part of the grand design. Obama

would spend his first year seeking bipartisan consensus,

and then when it was clear to one and all that the

Republicans were hopeless obstructionists, he'd spring

the trap.

The reality was a lot messier. Obama's administration

was all over the place strategically, and only came to

presidential toughness belatedly and as a last resort.

But Obama's behavior during the past two weeks does

remind us why we saw great things in this man, and

better late than never.

Robert Kuttner is co-editor of The American Prospect and

a senior fellow at Demos. His forthcoming book is A

Presidency in Peril.

The Original

The End of an Illusion

Robert Kuttner

Co-Founder and Co-Editor of The American

Prospect

March 14, 2010 10:30 PM

Are we at a turning point in the Obama presidency? It

took far too long, but the president has belatedly

grasped that when the other party is out to destroy you,

the search for common ground is a fool's errand.

For over a year, Obama believed that reform required him

to govern as a post-ideological bipartisan. Now,

mercifully, he has learned that progressive leadership

demands taking on the Republicans, just as it requires

taking on the insurance and banking industries. There is

little common ground on those fronts either.

Since early March, Obama has begun to sound more like

the bold figure who won the hearts of voters during the

campaign. The showdown is expected late next week.

Speaker Nancy Pelosi seldom schedules a vote without

having a majority in her pocket. With all the bill's

deficiencies, winning its passage would be a triumph,

not just for expansion of health coverage, but for

Obama's capacity to learn and grow in office and defeat

Republican obstruction.

Should he succeed, there will be little public sympathy

for Republican caviling about the use of the

reconciliation progress to, well, reconcile differences

between the House and Senate bills. Technical

parliamentary complaints will seem more like the

bleating of sore losers. Obama can seize the high ground

of majority rule.

And thanks to the sheer extremism of episodes like Sen.

Jim Bunning's attempted blockage of unemployment

insurance, Liz Cheney's association of lawyers honoring

the constitutional right to legal counsel with treason;

and the refusal of Congressional Republicans to back

even token recovery spending, Obama is well positioned

to define a new political mainstream even as he becomes

a more effective partisan progressive.

This odyssey was not an easy journey, and it is far from

complete. Obama's belief in common ground runs very deep

in his being. It remains to be seen whether his

reluctant embrace of partisanship to win the health

reform battle marks a durable change in his governing

style, or a one-off. But a victory on this defining

issue, after months of defeatism, would surely taste

sweet and would very likely mark a shift in Obama's

conception of leadership.

I say all this despite serious misgivings about the

health plan itself. The compulsory mandate is a

fundamental flaw, as Obama himself recognized during the

campaign. There is a world of difference between true

social insurance and a mandate to purchase a private

product. The former reinforces the value of government

and of social solidarity; the latter signals a coercive

state in concert with private industry profits. The

proposed tax on decent insurance was a tone-deaf assault

on wage earners for whom good health coverage is a rare,

reliable island in a rising sea of economic insecurity.

The diversion of Medicare funds was a political gift to

Republicans. And the back-loading of benefits purely for

budgetary reasons made the bill a political piñata, with

the risks evident and the gains deferred.

All of these elements made the plan a harder sell with

legislators of Obama's own party -- but all can be

fixed. At the end of the day, even Congressional

Democrats who worried that voters might punish them for

supporting this measure grasped a more fundamental

political truth: winning beats losing. There will be

time to improve the bill, particularly now that

Democrats have given themselves permission to use

majority rule rather than defer to Republican

obstruction.

Obama's new stance also serves as a role model. Senate

Banking Chairman Chris Dodd's belated abandonment of a

futile bipartisan approach to financial reform provides

a bookend to the president's new partisan leadership on

health reform.

Obama has also just appointed three relative

progressives to the Federal Reserve, including Sarah

Bloom Raskin of Maryland, widely considered the best of

the state financial regulators. There is not a single

businessman or banker in the lot.

Including in the health package an overhaul of the

student loan program, long blocked in the senate, is

another welcome demonstration of presidential nerve. But

prevailing on this first round of health reform will be

just the first step on a long road back.

Though both Obama and the Republicans treated health

reform as the defining issue of his presidency, other

challenges loom far larger. Obama has to do better on

employment, mortgage relief, and financial reform. He

has to deliver more tangible help to people for whom

this recovery still feels like a depression.

Presidential leadership has been crowded out by the

grand distraction of health reform and by Obama's own

reluctance to think bigger and fight harder. In these

critical areas too, corporate and partisan adversaries

have blocked progress. For this to be a true turning

point, his new-found partisanship and bolder progressive

stance must extend to the larger enterprise of restoring

prosperity.

If Obama wins health reform, and goes on to fight harder

for a real recovery program, some future historian

(doubtless guided by extended interviews with Rahm

Emanuel) will report that this latest turn to aggressive

partisanship was all part of the grand design. Obama

would spend his first year seeking bipartisan consensus,

and then when it was clear to one and all that the

Republicans were hopeless obstructionists, he'd spring

the trap.

The reality was a lot messier. Obama's administration

was all over the place strategically, and only came to

presidential toughness belatedly and as a last resort.

But Obama's behavior during the past two weeks does

remind us why we saw great things in this man, and

better late than never.

Robert Kuttner is co-editor of The American Prospect and

a senior fellow at Demos. His forthcoming book is A

Presidency in Peril.

The Original

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment