Tuesday, October 14, 2008

Stanley Fish on the Classroom and Buttons and Bows

October 12, 2008, 9:30 pm

Buttons and Bows

By Stanley Fish

Campaign buttons are a staple of any political season, but this year they are also central to yet another dispute about the rights of classroom teachers. The dispute has both a K-12 and a college version. In New York City, Department of Education Chancellor Joel Klein announced that his administration would enforce a longstanding policy prohibiting teachers from wearing campaign buttons when they are at work. In Illinois, the state university ethics office stated in its newsletter that faculty are barred not only from wearing campaign buttons in the classroom, but also from placing political bumper stickers on their cars and attending political rallies on campus.

Reaction was swift and predictable. In a letter to Chancellor Klein, United Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten noted that teachers have always “been allowed to express their opinions as citizens, political and otherwise, on their lapels.” American Association of University Professors President Cary Nelson (an emeritus professor at the University of Illinois, Urbana) issued a statement deploring the “chilling effect on speech” of such rules, which, he says, amount to “interference with the educational process.” He asks why “students can exercise their constitutional rights and attend rallies and wear buttons advocating candidates, but faculty cannot?”

There’s a lot to sort out here, and we might begin by separating the real issues from the silly ones.

It is silly (and unconstitutional) to dictate what faculty members can put on their cars, especially at a state university like Illinois where the parking lots are the size of Rhode Island and the odds of a student knowing which car belongs to which professor are next to nothing. At a more intimate liberal arts college, students might be aware of what cars their teachers drive, but it is unreasonable to require that students be shielded from any knowledge of professors’ political views, unless you want to say that faculty members can’t write letters to the editor because students might read them, and no one wants to say that.

The ban against attending political rallies is a closer call. On a campus with a small number of students and faculty, all of whom interact daily in a limited number of courses, there might be a worry that going directly from a rally into a classroom would run the risk of blurring the line between pedagogy and politics.

But again the risk seems too attenuated to justify a policy designed to minimize it. Joseph White, president of the University of Illinois, seems to agree, for on Oct. 6 he clarified (or, rather, backed down from) the ethics office’s memo and announced that university employees may “attend political rallies, provided that the employees are not on duty” and may also “display partisan bumper stickers on their vehicles.” (I would ban bumper stickers on aesthetic grounds, but that’s besides today’s point.)

That leaves the campaign buttons. On that matter, which is the real deal, White says that university employers may wear them so long they are not “on duty nor in the workplace.”

While there might be an argument about what is or is not “in the workplace,” classrooms surely are. So presumably the ban on professors wearing political buttons in class stands. Some of those protesting the restriction want to assimilate it to the attempt to regulate bumper stickers. Sherman Dorn acknowledges (on his blog) that “you can’t use public property to support candidates,” but “I assume,” he says, that “faculty buy their own clothes, so they’re festooning personal property” in the same way they festoon their personally owned vehicles.

But the issue is not whether the clothes or, for that matter, the buttons, belong to the teachers; the issue is what they’re using them for; and if they’re using them as political billboards — announcing their partisan identifications from their chests — the question of the intrusion of politics in the classroom cannot be avoided.

One way of answering it is to claim, as Leo Casey does, that teachers who wear campaign buttons are performing a valuable educational purpose. Rather than harm, he says, there is “some worthwhile good in students knowing that their teachers were engaged in the primary right and responsibility of citizenship-participation in the political process.”

But you don’t have to be overtly partisan in order to proclaim the virtue of participating in the political process. You can get that message across with a button that reads “I will vote on November 4th” or “Voting sustains Democracy.” A button that says Obama or McCain says only one thing: I’m for this guy and you should be, too. It doesn’t advance democracy; it advances a party.

Randi Weingarten’s failure to see this distinction is almost comical. She begins a sentence by saying that “teachers understand they cannot proselytize their personal beliefs” and ends it by saying that “they also understand the importance of showing students the value of civic participation.” But in what way is wearing a campaign button different from proselytizing your personal beliefs? You don’t have to be taking up a collection for a candidate in order to make a pitch for him. A campaign button will do just fine, and the student who sees it day after day will wonder if it might be prudent to slant an essay in a certain direction.

And as for Cary Nelson’s point (which others also make) that if students can wear campaign buttons, why can’t teachers too, the answer is obvious: if I look out and see Heather and Kevin turning themselves into advertisements for a candidate, my behavior doesn’t alter at all; but if they look up and see me announcing where I stand, they might well alter their behavior in ways of which they are not even aware. Faculty advocacy, even if it is technically silent, distorts and pollutes the educational process.

But what about a faculty member’s rights? This is the most often voiced objection to the button ban. It curtails the constitutionally protected speech of teachers. In a letter to President White, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Higher Education (an organization with whose positions I usually agree) cites Tinker v. Des Moines (1969) and its famous statement that “It can hardly be argued that either teachers or students shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the school house gate.” But as it turns out, this ringing declaration is merely flag-waving, for after delivering it the court announces a test (there’s always a test) that determines whether or not an abridgment of speech rights is O.K.: Does the speech at issue “materially disrupt the work and discipline of the school?”

In this case the school district did not allege any such disruption and so the majority ruled for the students who had been disciplined for wearing black armbands in protest of the Vietnam War. But the test opens the way for schools (and colleges) to argue that a particular form of speech does constitute a disruption, and subsequent cases have veered in the direction of Justice Black’s dissenting view that students and teachers do not have the right to “use the schools at their whim as a platform for the exercise of free speech,” if only because teachers are “hired to teach” and it is no business of the schools “to broadcast political or any other views to educate and inform the public.”

Justice Harlan, also writing in dissent, added that unless the regulation was designed “to prohibit the expression of an unpopular view,” schools officials “should be accorded the widest authority in maintaining discipline and good order in their institutions.” Harlan points in the direction of a conclusion I would endorse.

Restricting the behavior of teachers and students is in most cases a matter not of constitutional rights but of workplace requirements. FIRE castigates Illinois for denying its faculty “the right to engage in simple political speech like wearing campaign buttons.”

But the university does no such thing. When faculty members are not in class, they remain free to sport their buttons (White remarks that “many parts of campus are not workplaces”), and when they leave the campus, the university has no say at all about what they do or do not wear. The university’s judgment is that political speech does not belong in the classroom, which no more denies a teacher’s constitutional rights than a hospital would deny a nurse’s rights if it disciplined her for advocating for better working conditions in the middle of an operation.

My point is made for me by William Van Alstyne, past President of the AAUP and one of the world’s leading authorities on the first amendment. In a letter to current president Nelson, Van Alstyne corrects his view that faculty “have a first amendment right” to wear campaign buttons. “I have no doubt at all,” he declares, “that a university rule disallowing faculty members from exhibiting politically-partisan buttons in the classroom is not only not forbidden by the first amendment; rather, it is a perfectly well-justified policy that would easily be sustained against a faculty member who disregards the policy.”

Right! It’s no big deal. It’s a policy matter, not a moral or philosophical matter, and as long as the policy is reasonably related to the institution’s purposes, it raises no constitutional issues at all. On Oct. 10, the United Federation of Teachers filed suit to reverse the button ban, claiming that the free speech rights of teachers had been violated. If that’s their case, they’ll lose.

Buttons and Bows

By Stanley Fish

Campaign buttons are a staple of any political season, but this year they are also central to yet another dispute about the rights of classroom teachers. The dispute has both a K-12 and a college version. In New York City, Department of Education Chancellor Joel Klein announced that his administration would enforce a longstanding policy prohibiting teachers from wearing campaign buttons when they are at work. In Illinois, the state university ethics office stated in its newsletter that faculty are barred not only from wearing campaign buttons in the classroom, but also from placing political bumper stickers on their cars and attending political rallies on campus.

Reaction was swift and predictable. In a letter to Chancellor Klein, United Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten noted that teachers have always “been allowed to express their opinions as citizens, political and otherwise, on their lapels.” American Association of University Professors President Cary Nelson (an emeritus professor at the University of Illinois, Urbana) issued a statement deploring the “chilling effect on speech” of such rules, which, he says, amount to “interference with the educational process.” He asks why “students can exercise their constitutional rights and attend rallies and wear buttons advocating candidates, but faculty cannot?”

There’s a lot to sort out here, and we might begin by separating the real issues from the silly ones.

It is silly (and unconstitutional) to dictate what faculty members can put on their cars, especially at a state university like Illinois where the parking lots are the size of Rhode Island and the odds of a student knowing which car belongs to which professor are next to nothing. At a more intimate liberal arts college, students might be aware of what cars their teachers drive, but it is unreasonable to require that students be shielded from any knowledge of professors’ political views, unless you want to say that faculty members can’t write letters to the editor because students might read them, and no one wants to say that.

The ban against attending political rallies is a closer call. On a campus with a small number of students and faculty, all of whom interact daily in a limited number of courses, there might be a worry that going directly from a rally into a classroom would run the risk of blurring the line between pedagogy and politics.

But again the risk seems too attenuated to justify a policy designed to minimize it. Joseph White, president of the University of Illinois, seems to agree, for on Oct. 6 he clarified (or, rather, backed down from) the ethics office’s memo and announced that university employees may “attend political rallies, provided that the employees are not on duty” and may also “display partisan bumper stickers on their vehicles.” (I would ban bumper stickers on aesthetic grounds, but that’s besides today’s point.)

That leaves the campaign buttons. On that matter, which is the real deal, White says that university employers may wear them so long they are not “on duty nor in the workplace.”

While there might be an argument about what is or is not “in the workplace,” classrooms surely are. So presumably the ban on professors wearing political buttons in class stands. Some of those protesting the restriction want to assimilate it to the attempt to regulate bumper stickers. Sherman Dorn acknowledges (on his blog) that “you can’t use public property to support candidates,” but “I assume,” he says, that “faculty buy their own clothes, so they’re festooning personal property” in the same way they festoon their personally owned vehicles.

But the issue is not whether the clothes or, for that matter, the buttons, belong to the teachers; the issue is what they’re using them for; and if they’re using them as political billboards — announcing their partisan identifications from their chests — the question of the intrusion of politics in the classroom cannot be avoided.

One way of answering it is to claim, as Leo Casey does, that teachers who wear campaign buttons are performing a valuable educational purpose. Rather than harm, he says, there is “some worthwhile good in students knowing that their teachers were engaged in the primary right and responsibility of citizenship-participation in the political process.”

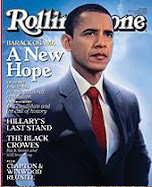

But you don’t have to be overtly partisan in order to proclaim the virtue of participating in the political process. You can get that message across with a button that reads “I will vote on November 4th” or “Voting sustains Democracy.” A button that says Obama or McCain says only one thing: I’m for this guy and you should be, too. It doesn’t advance democracy; it advances a party.

Randi Weingarten’s failure to see this distinction is almost comical. She begins a sentence by saying that “teachers understand they cannot proselytize their personal beliefs” and ends it by saying that “they also understand the importance of showing students the value of civic participation.” But in what way is wearing a campaign button different from proselytizing your personal beliefs? You don’t have to be taking up a collection for a candidate in order to make a pitch for him. A campaign button will do just fine, and the student who sees it day after day will wonder if it might be prudent to slant an essay in a certain direction.

And as for Cary Nelson’s point (which others also make) that if students can wear campaign buttons, why can’t teachers too, the answer is obvious: if I look out and see Heather and Kevin turning themselves into advertisements for a candidate, my behavior doesn’t alter at all; but if they look up and see me announcing where I stand, they might well alter their behavior in ways of which they are not even aware. Faculty advocacy, even if it is technically silent, distorts and pollutes the educational process.

But what about a faculty member’s rights? This is the most often voiced objection to the button ban. It curtails the constitutionally protected speech of teachers. In a letter to President White, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Higher Education (an organization with whose positions I usually agree) cites Tinker v. Des Moines (1969) and its famous statement that “It can hardly be argued that either teachers or students shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the school house gate.” But as it turns out, this ringing declaration is merely flag-waving, for after delivering it the court announces a test (there’s always a test) that determines whether or not an abridgment of speech rights is O.K.: Does the speech at issue “materially disrupt the work and discipline of the school?”

In this case the school district did not allege any such disruption and so the majority ruled for the students who had been disciplined for wearing black armbands in protest of the Vietnam War. But the test opens the way for schools (and colleges) to argue that a particular form of speech does constitute a disruption, and subsequent cases have veered in the direction of Justice Black’s dissenting view that students and teachers do not have the right to “use the schools at their whim as a platform for the exercise of free speech,” if only because teachers are “hired to teach” and it is no business of the schools “to broadcast political or any other views to educate and inform the public.”

Justice Harlan, also writing in dissent, added that unless the regulation was designed “to prohibit the expression of an unpopular view,” schools officials “should be accorded the widest authority in maintaining discipline and good order in their institutions.” Harlan points in the direction of a conclusion I would endorse.

Restricting the behavior of teachers and students is in most cases a matter not of constitutional rights but of workplace requirements. FIRE castigates Illinois for denying its faculty “the right to engage in simple political speech like wearing campaign buttons.”

But the university does no such thing. When faculty members are not in class, they remain free to sport their buttons (White remarks that “many parts of campus are not workplaces”), and when they leave the campus, the university has no say at all about what they do or do not wear. The university’s judgment is that political speech does not belong in the classroom, which no more denies a teacher’s constitutional rights than a hospital would deny a nurse’s rights if it disciplined her for advocating for better working conditions in the middle of an operation.

My point is made for me by William Van Alstyne, past President of the AAUP and one of the world’s leading authorities on the first amendment. In a letter to current president Nelson, Van Alstyne corrects his view that faculty “have a first amendment right” to wear campaign buttons. “I have no doubt at all,” he declares, “that a university rule disallowing faculty members from exhibiting politically-partisan buttons in the classroom is not only not forbidden by the first amendment; rather, it is a perfectly well-justified policy that would easily be sustained against a faculty member who disregards the policy.”

Right! It’s no big deal. It’s a policy matter, not a moral or philosophical matter, and as long as the policy is reasonably related to the institution’s purposes, it raises no constitutional issues at all. On Oct. 10, the United Federation of Teachers filed suit to reverse the button ban, claiming that the free speech rights of teachers had been violated. If that’s their case, they’ll lose.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment