Friday, October 31, 2008

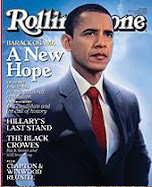

Is Barack's Story an American Story???

Below Roger Cohen paints a very interesting picture of Barack Obama and his story. He begins by testing Barack Obama’s assertion that “in no other country on earth is my story possible.” Having just returned from South Africa, one wonders if Nelson Mandela, a black man, felt the same way when he became president of a white supremacist capitalist nation? While there may be some parallels, Nelson Mandela’s presidency was to quell a more bloody transition in a nation in which blacks are 90% of the population. Though having a white supremacist past, the United States has a very different history with blacks as a gross minority. To have a majority white nation with such strong ties to a white Europe elect a black man president is unique. Nowhere else could this happen. As Cohen notes the election of Obama would be that of a man “…whose very identity represents an act of reconciliation...toward building change….” To the extent that is reality, Barack’s story is a new American story and represents a new chapter in American history. RGN

October 30, 2008

Op-Ed Columnist

American Stories

By ROGER COHEN

Of the countless words Barack Obama has uttered since he opened his campaign for president on an icy Illinois morning in February 2007, a handful have kept reverberating in my mind:

“For as long as I live, I will never forget that in no other country on earth is my story even possible.”

Perhaps the words echo because I’m a naturalized American, and I came here, like many others, seeking relief from Britain’s subtle barriers of religion and class, and possibility broader than in Europe’s confines.

Perhaps they resonate because, having South African parents, I spent part of my childhood in the land of apartheid, and so absorbed as an infant the humiliation of racial segregation, the fear and anger that are the harvest of hurt — just as they are, in Obama’s words, “the brutal legacy of slavery and Jim Crow.”

Perhaps they speak to me because I live in New York and watch every day a miracle of civility emerge from the struggles and fatigue of people drawn from every corner of the globe to the glimmer of possibility at the tapering edge of the city’s ruler-straight canyons.

Perhaps they move me because the possibility of stories has animated my life; and no nation offers a blanker page on which to write than America.

Or perhaps it’s simply because those 22 words cleave the air with the sharp blade of truth.

Nowhere else could a 47-year-old man, born, as he has written, of a father “black as pitch” and a mother “white as milk,” a generation distant from the mud shacks of western Kenya, raised for a time as Barry Soetoro (his stepfather’s family name) in Muslim Indonesia, then entrusted to his grandparents in Hawaii — nowhere else could this Barack Hussein Obama rise so far and so fast.

It’s for this sense of possibility, and not for grim-faced dread, that people look to America, which is why the Obama campaign has stirred such global passions.

Americans are decent people. They’re not interested in where you came from. They’re interested in who you are. That has not changed.

But much has in the last eight years. This is a moment of anguish. The Bush presidency has engineered the unlikely double whammy of undermining free-market capitalism and essential freedoms, the nation’s twin badges.

American luster is gone. The American idea has, in Joyce Carol Oates’s words, become a “cruel joke.” Americans are worrying and hurting.

So it is important to step back, from the last machinations of this endless campaign, and think again about what America is.

It is renewal, the place where impossible stories get written.

It is the overcoming of history, the leaving behind of war and barriers, in the name of a future freed from the cruel gyre of memory.

It is reinvention, the absorption of one identity in something larger — the notion that “out of many, we are truly one.”

It is a place better than Bush’s land of shadows where a leader entrusted with the hopes of the earth cannot find within himself a solitary phrase to uplift the soul.

Multiple polls now show Obama with a clear lead. But nobody can know the outcome and nobody should underestimate the immense psychological leap that sending a black couple to the White House would represent.

What I am sure of is this: an ever more interconnected world, where financial chain reactions spread with the virulence of plagues, thirsts for American renewal and a form of American leadership sensitive to humanity’s tied fate.

I also know that this biracial politician, the Harvard graduate who gets whites because he was raised by them, the Kenyan’s son who gets blacks because it was among them that mixed race placed him, is an emblematic figure of the border-hopping 21st century. He is the providential mestizo whose name — O-Ba-Ma — has the three-syllable universality of some child’s lullaby.

And what has he done? What does his experience amount to? Does his record not demonstrate he’s a radical? The interrogation continues. It’s true that his experience is limited.

But Americans seem to be trusting what their eyes tell them: temperament trumps experience and every instinct of this man, whose very identity represents an act of reconciliation, hones toward building change from the center.

Earlier this year, at the end of a road of reddish earth in western Kenya, I found Obama’s half-sister Auma. “He can be trusted,” she said, “to be in dialogue with the world.”

Dialogue, between Americans and beyond America, has been a constant theme. Last year, I spoke to Obama, who told me: “Part of our capacity to lead is linked to our capacity to show restraint.”

Watching the way he has allowed his opponents’ weaknesses to reveal themselves, the way he has enticed them into self-defeating exhaustion pounding against the wall of his equanimity, I have come to understand better what he meant.

Stories require restraint, too. Restraint engages the imagination, which has always been stirred by the American idea, and can be once again.

October 30, 2008

Op-Ed Columnist

American Stories

By ROGER COHEN

Of the countless words Barack Obama has uttered since he opened his campaign for president on an icy Illinois morning in February 2007, a handful have kept reverberating in my mind:

“For as long as I live, I will never forget that in no other country on earth is my story even possible.”

Perhaps the words echo because I’m a naturalized American, and I came here, like many others, seeking relief from Britain’s subtle barriers of religion and class, and possibility broader than in Europe’s confines.

Perhaps they resonate because, having South African parents, I spent part of my childhood in the land of apartheid, and so absorbed as an infant the humiliation of racial segregation, the fear and anger that are the harvest of hurt — just as they are, in Obama’s words, “the brutal legacy of slavery and Jim Crow.”

Perhaps they speak to me because I live in New York and watch every day a miracle of civility emerge from the struggles and fatigue of people drawn from every corner of the globe to the glimmer of possibility at the tapering edge of the city’s ruler-straight canyons.

Perhaps they move me because the possibility of stories has animated my life; and no nation offers a blanker page on which to write than America.

Or perhaps it’s simply because those 22 words cleave the air with the sharp blade of truth.

Nowhere else could a 47-year-old man, born, as he has written, of a father “black as pitch” and a mother “white as milk,” a generation distant from the mud shacks of western Kenya, raised for a time as Barry Soetoro (his stepfather’s family name) in Muslim Indonesia, then entrusted to his grandparents in Hawaii — nowhere else could this Barack Hussein Obama rise so far and so fast.

It’s for this sense of possibility, and not for grim-faced dread, that people look to America, which is why the Obama campaign has stirred such global passions.

Americans are decent people. They’re not interested in where you came from. They’re interested in who you are. That has not changed.

But much has in the last eight years. This is a moment of anguish. The Bush presidency has engineered the unlikely double whammy of undermining free-market capitalism and essential freedoms, the nation’s twin badges.

American luster is gone. The American idea has, in Joyce Carol Oates’s words, become a “cruel joke.” Americans are worrying and hurting.

So it is important to step back, from the last machinations of this endless campaign, and think again about what America is.

It is renewal, the place where impossible stories get written.

It is the overcoming of history, the leaving behind of war and barriers, in the name of a future freed from the cruel gyre of memory.

It is reinvention, the absorption of one identity in something larger — the notion that “out of many, we are truly one.”

It is a place better than Bush’s land of shadows where a leader entrusted with the hopes of the earth cannot find within himself a solitary phrase to uplift the soul.

Multiple polls now show Obama with a clear lead. But nobody can know the outcome and nobody should underestimate the immense psychological leap that sending a black couple to the White House would represent.

What I am sure of is this: an ever more interconnected world, where financial chain reactions spread with the virulence of plagues, thirsts for American renewal and a form of American leadership sensitive to humanity’s tied fate.

I also know that this biracial politician, the Harvard graduate who gets whites because he was raised by them, the Kenyan’s son who gets blacks because it was among them that mixed race placed him, is an emblematic figure of the border-hopping 21st century. He is the providential mestizo whose name — O-Ba-Ma — has the three-syllable universality of some child’s lullaby.

And what has he done? What does his experience amount to? Does his record not demonstrate he’s a radical? The interrogation continues. It’s true that his experience is limited.

But Americans seem to be trusting what their eyes tell them: temperament trumps experience and every instinct of this man, whose very identity represents an act of reconciliation, hones toward building change from the center.

Earlier this year, at the end of a road of reddish earth in western Kenya, I found Obama’s half-sister Auma. “He can be trusted,” she said, “to be in dialogue with the world.”

Dialogue, between Americans and beyond America, has been a constant theme. Last year, I spoke to Obama, who told me: “Part of our capacity to lead is linked to our capacity to show restraint.”

Watching the way he has allowed his opponents’ weaknesses to reveal themselves, the way he has enticed them into self-defeating exhaustion pounding against the wall of his equanimity, I have come to understand better what he meant.

Stories require restraint, too. Restraint engages the imagination, which has always been stirred by the American idea, and can be once again.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment