Needless to say, the bankruptcy of conservatism is the reality all around us. Fortunately, this time unlike 2004, or 2000 for that matter, an election that was accepted as legitimate, Bush and Cheney have disgraced even America's right wing. The electorate will not be fooled this time. McCain's healhcare plan is just another example of that bankruptcy. The bigotry of Jesse Helms was buried yesterday. Hopefully the white nationalism of the Reagan Revolution will be buried on November 4th. RGN

July 9, 2008

McCain Plan to Aid States on Health Could Be Costly

By KEVIN SACK

PIKESVILLE, Md. — If Senator John McCain’s radical plan for remaking American health care is to work, he will have to find a way to cover people like Chaim Benamor, 52, a self-employed renovator in this Baltimore suburb. Mr. Benamor never found it necessary to buy insurance before having a mild heart attack last year and now, 13 years shy of Medicare, has little hope of doing so.

The heart attack left Mr. Benamor with a $17,000 hospital bill, $400 in monthly prescription costs and a desperate need for insurance. After being rejected by a number of commercial carriers, he turned to the Maryland Health Insurance Plan, one of 35 state programs for high-risk applicants whom no private company is willing to insure.

He decided that the annual premium — $4,572 for a plan with heavy deductibles — was more than he could handle on an income of about $35,000. Yet his earnings were too high for him to qualify for state subsidies.

“I’d like to get it, but what do you pay first?” Mr. Benamor asked at his dining room table. “Do you pay the mortgage? Do you pay your child support? Do you pay your car insurance? Do you pay for your medicine?”

In late April, Mr. McCain, Republican of Arizona, announced that if elected president he would seek to insure people like Mr. Benamor by vastly expanding federal support for state high-risk pools like Maryland’s, or by creating a structure modeled after them. But as Mr. Benamor’s case demonstrates, even well-regarded pools have served more as a stopgap than a solution.

Though high-risk pools have existed for three decades, they cover only 207,000 people in a country with 47 million uninsured, according to the National Association of State Comprehensive Health Insurance Plans. Premiums typically are high, as much as twice the standard rate in some states, but are still not nearly enough to pay claims. That has left states to cover about 40 percent of the cost, usually through assessments on insurance premiums that are often passed on to consumers.

Health economists say it could take untold billions to transform the patchwork of programs into a viable federal safety net. The McCain campaign has made only a rough calculation of how many billions would be needed and has not identified a source for the fi-nancing beyond savings from existing programs. Finding the money will only get more difficult now that Mr. McCain has pledged to balance the federal budget by 2013, which already requires a significant reduction in the growth of spending.

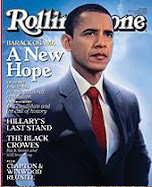

Mr. McCain’s proposal stands in sharp relief to that of his Democratic rival, Senator Barack Obama of Illinois, who wants to require insurers to accept all applicants, regardless of their health. That is now the law in five states, including New York and New Jersey.

For those who can afford the premiums, or who qualify for subsidies in the 13 states that provide them, the high-risk programs can be a godsend.

Richard and Susan Logan, both of whom have battled cancer this decade, said they were grateful to have coverage for themselves and their daughter through the Maryland plan, even though it will cost $22,232 this year. They had been rejected by 25 commercial insurers, said Mrs. Logan, 57, a part-time billing clerk for a physician.

The Logans, who live in Gambrills, near Annapolis, estimate that without the high-risk pool, they would pay $40,000 a year for medication alone.

“The plan’s worth its weight in gold for that,” said Mr. Logan, 62, an aviation accident investigator. “Otherwise, we’d be paying for the medications out of our retirement.”

A fifth of the 14,000 participants in the Maryland plan receive subsidies that drop their premiums below the market rates charged to healthy people, said Richard A. Popper, the plan’s director. But many in the middle find the policies both unaffordable and intolerably restrictive, and Mr. Popper estimates that two-thirds of those eligible have not enrolled.

Almost all of the state pools impose waiting periods of up to a year before covering the health conditions that initially made it impossible to obtain insurance. In some states, fiscal pressures have forced heavy restrictions in coverage and enrollment. Florida, which has 3.8 million uninsured people, closed its pool to new applicants in 1991, and the membership has dwindled to 313.

An informal survey by the American Cancer Society recently found that only 2 percent of nearly 2,700 callers to its insurance hot line enrolled in high-risk pools within two months of being referred to them. “In most cases, we know they probably didn’t apply because they discovered high premiums or pre-existing condition clauses and just didn’t bother,” said Stephen Finan, associate director of policy for the group’s Cancer Action Network.

There is no census of the medically uninsurable. But in 2006, insurers turned down 11 percent of all individual applicants for medical reasons, including 22 percent of those 50 or older, according to America’s Health Insurance Plans, an industry trade group.

Finding a way to cover the sickest of the uninsured is critically important because 15 percent of the population is responsible for three-fourths of health care spending. Many wind up in emergency rooms, which cannot legally reject them, leaving hospitals with more than $30 billion in unpaid bills each year.

Mr. McCain’s proposal, which he calls the Guaranteed Access Plan, would be part of a market-based restructuring that is in many ways more fundamental than the universal coverage proposed by Mr. Obama.

With the goal of making the insurance marketplace more equitable and competitive, Mr. McCain would end the longstanding exclusion from income taxes of health benefits paid by employers. The 17 million nonelderly people covered by directly purchased insurance do not enjoy that advantage.

Mr. McCain would replace the exclusion with refundable health care tax credits of $2,500 per person and $5,000 per family in the hope of driving consumers into the individual insurance market. To help push down premiums, he would allow the purchase of policies across state lines.

Currently, those who buy insurance individually often face higher costs because their risks are not spread across broad groups of workers. Though insurers cannot discriminate against participants in group plans, they evaluate consumers seeking individual coverage case by case to determine if they are worth the risk of coverage, and at what price. Insurers contend that if they had to charge the same rates to all comers, many would wait until they were sick to buy policies.

The McCain campaign recognizes that in an invigorated individual market, even larger numbers of chronically ill people would go without the protection afforded by group coverage. High-risk pools would theoretically serve to fill the gaps.

Critics argue that, to date, insurers have benefited from the state pools as much as the uninsured. As long as premiums remain above market rates, the pools insulate commercial insurers from the greatest risks while giving customers little incentive to abandon their private policies.

“They are run in ways that protect the profitability of commercial insurers,” said Karen Pollitz, a professor at Georgetown University who has studied high-risk pools and who has served on the board of the Maryland plan. “They leave the illusion that there’s a safety net without there really being much of one.”

Mr. Obama’s plan differs from Mr. McCain’s in several ways. In addition to requiring insurers to accept all applicants, he would require that parents obtain insurance for their children. To make premiums affordable, he would create a Medicare-like government plan that would be open to all and pump up to $65 billion a year into subsidies. The money would come from repealing President Bush’s income tax cuts for those earning more than $250,000 a year.

When Mr. McCain unveiled his high-risk pool proposal, his chief domestic policy adviser, Douglas Holtz-Eakin, the former director of the Congressional Budget Office, estimated the federal cost at $7 billion to $10 billion. Mr. Holtz-Eakin said five million to seven million uninsured people would be singled out for coverage.

But in a recent interview, Mr. Holtz-Eakin emphasized that the projections “could change dramatically” depending on how the program was structured.

Mr. Holtz-Eakin and other McCain health advisers, including Thomas P. Miller, a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and Stephen T. Parente, a health economist at the University of Minnesota, said premiums would probably be capped at twice the standard rates. They said subsidies might be available to those making up to four times the federal poverty level, or $41,600 for a single person.

Financial incentives would probably be provided to those who effectively manage their diseases. No decision has been made about waiting periods for pre-existing conditions, the advisers said.

Mr. McCain’s proposal would represent a huge increase over the $50 million a year that Congress now appropriates in grants to the state pools, in a program that began in 2002. But several analysts questioned whether even $10 billion would be nearly enough, given that the states now spend about $2 billion to insure 207,000 people.

“I do not for a minute think it will cost 7 to 10 billion dollars a year,” Ms. Pollitz said. “It may cost 7 to 10 billion dollars a week.”

In an admonition for Mr. McCain, Maryland’s five-year-old plan, like others before it, has quickly become a victim of its growth. As enrollment expanded by 30 percent in each of the last two years, actuaries forecast insolvency as soon as 2010 and compelled the plan’s board to apply the brakes.

Over the last two years, it has raised premiums, deductibles and co-payments, increased out-of-pocket maximums, lowered the lifetime cap on payments and added a waiting period for pre-existing conditions, which rose to six months from two months on July 1. It also increased the amount applicants must pay to buy their way out of the waiting period.

At the same time, the plan is making more people eligible for subsidies. To keep it afloat, the state is raising the assessment on hospital bills that provides two-thirds of its financing.

“It’s not easy when you see there is strong demand for something and you need to temper that demand,” Mr. Popper, the plan’s director, said. “But you either find a way to slow enrollment through economic forces or you close the plan and no one gets in, which is a solution that no one wants.”

No comments:

Post a Comment