Monday, April 26, 2010

The Obama Presidency and SNCC at 50 years

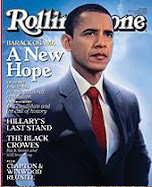

Having Obama as president is an historical event, particularly in the backdrop of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee's 50th anniversary celebration. It seems as though the Obama presidency presented conflicting perspectives for those in attendance. Congressman John Lewis who supported Clinton early on is a devoted supporter of Obama. He sees Obama as being "the bridge." Julian Bond reminded those gathered how far we have come and the role of SNCC in getting us here. The venerable Harry Belafonte at 83 years of age captivated the gathering by being proud of Obama's election but wondering what about the poor? The importance of SNCC cannot be overstated. They were the courageous souls organizing in government endorsed and government supported Klan country, the Jim Crow South. With them there is so much to celebrate. Without their courage in the face of murderous evil white supremacists, the changes would not have taken place to put Barack Obama in the White House. RGN

We’ll Never Turn Back: SNCC 50th Anniversary Celebrates Vanguard Role In Battles for Democracy

By CCDS Participants

More than 1100 people gathered at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina over the April 15-18 weekend for a 50th Anniversary gathering of the veterans of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and its close allies. SNCC was an early vanguard force in the Southern Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, as well as the Black Revolt that spread nationwide in its wake.

The reunion was an outpouring of powerful emotions, living history and inspiring visions of radical democratic change still needed in the politics of today. These were the people, now graying, who had put their bodies and their lives on the line to bring down Jim Crow segregation, gain Black political power and help end an unjust war in Vietnam. In the process, they had won major victories but were also well aware of work still to be done.

People travelled from every corner of the country to attend. They were Black and white, Asian and Chicano, and they came from all walks of life--some arrived in the bib blue jean overalls of the sharecroppers in the Deep South, while others wore dark business suits, colorful dashikis and everything in between. Most of all, their faces beamed with smiles. There were joyful and tearful embraces, many rooted in the pent-up sufferings and memories of those who had fallen, both at the time and over the years since.

"Many went to jail," said Chuck McDew, SNCC chairman from 1960 to 1963. "Many suffered. Many suffered brutalization at the hands of the law. ... While America is a different place because of SNCC, and many who have sacrificed over the years, the struggle continues."

For a gathering centered on 50-year veterans, the events in Raleigh were remarkably intergenerational. Students from Shaw and surrounding schools learned about it and decided to take part. Many of the SNCC veterans themselves brought their children and grandchildren. Most important, a large number of the SNCC activists were still engaged in organizing projects with younger generations, and these new activists attended with them.

Shaw University was important in more ways than providing a comfortable venue. It was truly a return to an historic site and source. For it was on this campus that the legendary Ella Josephine Baker and other civil rights organizers from the 1940s and 1950s called the founding conference of SNCC in 1960, inspiring and planning the events that followed.

“For all of the youthful energy and commitment to challenge and change that erupted in 1960,” said Charlie Cobb, a SNCC Field Secretary, “the reason for SNCC's existence comes down to one person—a then-57-year-old woman—Ella Baker, one of the great figures of 20th-century struggle. In a deep political sense, we are her children and our 50th anniversary conference is dedicated to her.”

The conference was structured over three-and-a-half days with large plenary gatherings alternating with a variety of choices of smaller, but still large sessions. The evenings featured cultural events and time for people to socialize and mix with old friends and new.

Highlights of the first plenaries were speeches by Julian Bond and the Rev. James Lawson. Neither minced any words about the ongoing source of the problem: the capitalist system and its structures of race, gender and class privilege. Julian Bond’s presentation was especially relevant.

"What began 50 years ago is not just history," Bond said. "It was part of a mighty movement that started many, many years before that and continues on to this day -- ordinary women, ordinary men proving they can perform extraordinary tasks in the pursuit of freedom."

“By 1965,” Bond continued, “SNCC fielded the largest staff of any civil rights organization operating in the South. It had organized nonviolent direct action against segregated facilities and voter registration projects in Alabama, Arkansas, Maryland, Missouri, Louisiana, Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Illinois, North and South Carolina, Georgia, Texas, and Mississippi.

“It had built two independent political parties and organized labor unions and agricultural co-operatives. It gave the movement for women's liberation new energy. It inspired and trained the activists who began the 'New Left.' It helped expand the limits of political debate within black America, and broadened the focus of the civil rights movement. Unlike mainstream civil rights groups, which merely sought integration of Blacks into the existing order, SNCC sought structural changes in American society itself…

“SNCC was in the vanguard in demonstrating that independent black politics could be successful. Its early attempts to use black candidates to raise issues in races where victory was unlikely expanded the political horizon. SNCC's development of independent political parties mirrored the philosophy that political form must follow function and that non-hierarchical organizations were essential to counter the growth of personality cults and self-reinforcing leadership.”

In part because of SNCC, Bond added, “Blacks have been elected to run the country, states and cities. And young blacks can go anywhere they choose. We played an important role and that role has never gotten the proper attention. But we did it because it was the right thing to do."

Bond went on to put the onus on imperialism, militarism and its wars. He had spent 20 years as a Georgia legislator, and had to beat back attempts to unseat him for his militant opposition to the Vietnam War. Later he went on to head up the NAACP, developing it in a more youth-oriented and progressive direction.

Lawson spoke later on the same theme, denouncing the ‘plantation capitalism’ that seeks a narrow financial resolution of the current economic crisis while leaving Blacks and lower-income workers generally in the lurch.

Six panels filled out the first day. Themes included the early philosophy of SNCC, how student activists integrated themselves with the rural poor and became field organizers, how SNCC grew as an organization, the societal response to SNCC, and ‘Up South’, the building of SNCC and Friends of SNCC outside of the Deep South. All of them included presenters widely known at the time—Charlie Cobb, Judy Richardson, Larry Rubin, D’Army Bailey, Tamio Wakanama, Betita Martinez, John Doar and many more.

In the panel on the “Impact of SNCC,” historian Taylor Branch spoke about the “broad democratization of politics” and “high emotion with deep thought.” Tom Hayden also declared, “We have to stand with the demonized until the demonizing ends.”

Ira Grupper, currently a CCDS national committee member from Louisville, Kentucky who earlier had served on the staff of SNCC in Georgia, as well as COFO (Council of Federated Organizations) and the MFDP (Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party) in Mississippi, also spoke during the question period. He reminded the audience that it was ordinary people, maids and janitors, who were the base, and that a joint force of the informally and formally educated was what built the movement.

But the talk of the conference was the speech by Harry Belafonte at a standing-room only lunch gathering on the second day. Now 83-years-old, the civil rights warrior and early SNCC supporter was as fiery and sharp as ever. Belafonte talked not only about the achievements of SNCC, but also the conditions of the day and the tasks undone.

"Most of what I'm hearing is about what was, and how well we did it," said Belafonte, challenging and chastising conference attendees in a hoarse, but determined voice of a wise griot. "We all know what was, and how well we did it. The question is, 'Who is talking about what is, and how badly we are doing it now?’ Yes, I'm proud that Barack Obama is president, but I find nothing that speaks to the issue of the poor. I find nothing that speaks to the issue of the disenfranchised. I find a lot of people rushing for cover anytime you criticize Barack Obama."'

Belafonte went on to praise the power and creativity of hip-hop culture, and how it had spread across the world. At the same time he denounced its treatment of women and its derailment by capitalism and the glorifications of ‘bling,’ the trappings of wealth. "Where is our voice?" Belafonte continued. "Why are we so soft? We have become too comfortable in too many ways, and we have to change." His message touched a raw nerve, but it sank in. He received a standing ovation.

One workshop that day put a spotlight on the high quality of the meetings. Entitled “More than a Hamburger,” it was referring to the original Woolworth counter sit-in and an exposition on the revolutionary implications of even the simplest battles for democracy. But the panelists present, all SNCC and Black freedom activists decades ago, also told a story in their own right in their own histories. Eleanor Holmes Norton, now a Member of Congress representing the District of Columbia and a distinguished lawyer, started as a young SNCC activist in the heady days of the Mississippi Summer Project. Gwen Patton, now a distinguished educator and theologian, came from a working-class family in Detroit to work with SNCC and SCLC in Alabama, and then headed up the National Black Antidraft and Antiwar Union.

There were more. Frank Smith, a District of Columbia Council Member, started as a SNCC field organizer in Georgia. Ed Brown, a UCC Minister, took leave from the church to engage in some the organizing work in parts of Mississippi most threatened with violence, where SNCC worker Sammy Younge had been murdered. Leah Wise, an executive director of the Southeast Regional Economic Justice Network and editor of Southern Exposure, started as a SNCC worker and went on to help the National Anti-Klan Network following the KKK killings in North Carolina in the 1970s. Doris Dozier Chrenshaw was a participant in the original Montgomery Bus Boycott sparked by Rosa Parks. Finally, Kathleen Cleaver, now with the Yale Law School, but formerly with the Black Panther Party and the New York City office of SNCC.

Any one of these individuals could have engaged hundreds of people for hours in a consciousness-raising dialogue. But this was only one workshop. Others that day, Thursday, focused on the SNCC projects in Mississippi, the projects in Alabama; where the Lowndes County Freedom Organization put up the Black Panther as its symbol and went on to win the election of a sheriff, the Border States efforts in Maryland and Northern Virginia, and the Southwest Georgia Project, where many tough battles were fought.

One remarkable cultural event later in the evening brought all this history and radical thought into one room. Entitled ‘Meet the Authors,’ it was held in a large banquet room at the Crabtree Marriot with tables lining all four walls. Here some 35 SNCC veterans displayed and autographed their latest books going into every aspect of the struggle—Bob Zellner’s ‘The Wrong Side of Murder Creek: A White Southerner in the Freedom Movement,’ John Dittmer’s ‘Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi,’ Charlie Cobb’s ‘On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Trail,’ and Betita Martinez’s ‘500 Years of Chicana Women's History,’ to name just a few. Hundreds of people stood in the room for hours, greeting old friends and discussing new ideas.

Beyond this room, the Crabtree Marriott served as a wider ‘SNCC Reunion Central’ over four days. Wander into the lobby anytime and you’d run into scenes like that of Kathleen Cleaver plugging away on her laptop while greeting old friends, and Jesse Jackson, walking through the lobby, shaking hands and greeting participants. In another corner of the lobby, there’d be Willie Ricks, the legendary firebrand of the ‘Black Power!’ slogan launched during the 250-mile ‘March Against Fear’ in 1966 Mississippi, holding forth with a circle of his friends, or Georgia State Senator Nan Grogan Orrock hugging old friends from the Southern student movement. Walk into the bar, and there’s Tom Hayden crowded with eight people around a table, having a great time solving the world’s problems. Walk further back, and there’s Kay and Walt Tillow, key organizers with the All-Unions Coalition for Single Payer, cornered with Carl Davidson, the old SDSer and current co-chair of Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism, arguing economic reforms and the path to socialism, as well as what to do about health care. And so on, night after night--bring this many politically experienced and engaged people together and there’s bound to be a high level of synergy.

The Friday workshops also presented hard choices: Depictions of the Movement in Popular Culture, Black Power/Education/Pan Africanism, The Role of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, Women Leaders and Organizers, The Black Church and the Black Struggle, Highlander, SSOC and Organizing the White Community, and SNCC in the Black Arts Movement. Any one person could only pick two.

Bob Zellner chaired the workshop on whites organizing among whites, which drew nearly 100 people. Introducing himself, Zellner said “I always tell people I was born in a police state, the state of Alabama. I also tell them my Daddy was a Bible thumping, robes-wearing Klansman, and so was my Grandpa. So that makes me born and bred in a police state and raised by fundamentalist terrorists.”

Zellner then reminded the attendees that he has never agreed with organizing whites solely as whites. He understood Blacks and other minority nationalities organizing their own forms, but he always thought it important that even if organizations were mainly made up of whites, that Blacks be included as well. “Otherwise you run into a dynamic that takes you to a bad place you don’t want to go.”

Sue Thrasher got the workshop rolling with her story of moving from being a small-town Southern farm girl to a leader in SNCC and SSOC, the Southern Student Organizing Committee. “I grew up on a farm in a rural West Tennessee county that borders North Mississippi and Alabama. My father was a farmer by choice and a carpenter by necessity. Shortly after I was born, my family moved to Oak Ridge, Tennessee where my father built housing for the defense workers who would ultimately build the atom bomb. My mother became a ‘Rosie’ of sorts, entering the work force for the first time driving an army payroll car.”

“I saw college as a way out. I was lucky. I arrived in Nashville in the fall of 1961, still a major hotbed of civil rights activities. The period from 1961 through 1966 revolutionized the shape of my life. My first tentative step to speak out on campus issues led to involvement in the local SNCC chapter, and eventually the broader southern movement. In the spring of 1964, I helped organize the founding conference of the Southern Students Organizing Committee (SSOC), an organization to grow and support fledgling civil rights activities on predominantly white campuses. I participated in Mississippi Summer as a member of the “white folks project” working in Jackson, Biloxi, and Hattiesburg. That fall, I opened SSOC’s office in Nashville and served as Executive Secretary for the next two years.”

Other panelists added to Thrasher’s account, going into descriptions of the importance of Anne Braden of SCEF and Myles Horton of the Highlander Center, where many future civil rights and labor leaders were schooled in radical methods of teaching and learning. Many stressed the ongoing importance of the Highlander Center, which is still thriving today near Knoxville, Tennessee. Zellner’s work in Mississippi, bringing together Black and white woodcutters in a single organization to fight for their rights and improve their condition, was cited as an example of what could be done.

CCDS’s Carl Davidson spoke from the floor on the current importance of the topic. In addition to working with SNCC in his SDS leadership role in the 1960s, Davidson was also a veteran of the 1966 ‘March against Fear’ in Mississippi.

“Where I work today, in the semi-rural townships of Western Pennsylvania,” Davidson commented, “if you organize at all, it’s among white workers, because that’s about all we have there. But we work closely with the labor movement, and we got a decent orientation from Richard Trumka, now head of the AFL-CIO. He told us to go door-to-door, and to meet any anti-Obama racism head-on, to tell people point blank to cast aside their prejudices or sit on them, and vote their best interests instead. That’s exactly what we did, and Trumka’s approach was picked up by union activists all across the state. Things are far from perfect, but it made a big difference in the election and in strengthening our alliances with African Americans still residing in the mill towns.”

Saturday morning’s main event took place in the sanctuary of the First Baptist Church in downtown Raleigh. Entitled ‘SNCC Veterans Introduce Their Children,’ an activity appropriate to any family gathering, and to many, SNCC was like family.

“While hundreds wept, clapped their hands and sang,” Tom Hayden reported in The Nation, “they came to the pulpit to declare themselves: Maisha Moses (Bob and Janet Moses), her brother Omo, James Forman Jr. (James Forman and Dinky Romilly), Tarik Smith (Frank and Jean Smith), Sabina Varela (Maria Varela and Lorenzo Zuniga), Bakari Sellers (Cleveland and Gwendolyn Sellers), Zora Cobb (Charles Cobb and Ann Chinn), Hollis Watkins Jr. (Hollis Watkins and Nayo Barbara Watkins), Gina Belafonte (Harry and Julie Belafonte).

“Sherry Bevel (James Bevel and Diane Nash) combined humor and compassion for her father, who was convicted of incest in 2008, released on appeal and died shortly afterward: “It would be a shame if his wit and energy was forgotten. We have had great men and women who were caught up in drug or alcohol problems, or were philandering with underage girls. But I for one don't think we should just forget Thomas Jefferson.”

She stated this turning of the tables softly, and with a sweet smile—and it brought down the house with laughter and applause.

The Saturday afternoon main session was a big deal, especially for the press. Attorney General Eric Holder was to speak, and be introduced by Congressman John Lewis, former national leader of SNCC. Lewis paid tribute to those SNCC members who were killed or beaten then in their pursuit of freedom, echoed Belafonte’s earlier concern at the conference, but also gave a rallying cry: "You've gone through the worst. You've been thrown in jail, you've been beaten. What can anyone do to you now? Make some noise.”

Lewis then turned the platform over to the Attorney General.

“On this historic day, as we celebrate the 50th Anniversary of SNCC’s beginnings,” said Holder, “I can’t help but be optimistic. And I can’t help but recall Dr. King’s prophetic reminder that "the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice." I believe that Dr. King was right, in part because of the progress I’ve witnessed during my own lifetime and the incredible healing I’ve seen.

“As a child in New York, I cheered on the Brooklyn Dodgers and their star second baseman, Jackie Robinson. As a boy, I watched Vivian Malone – a woman who later became my sister-in-law – step past George Wallace to integrate the University of Alabama. As a teenager, I felt the scope of my own dreams expand as I saw Thurgood Marshall take his historic place on our nation’s highest court. As a man, I’ve had the privilege to serve our nation’s first African-American President. And I now have the indescribable honor of leading our nation’s Justice Department as the first African-American Attorney General.

“This progress would not have, and could not have, occurred without SNCC’s work. Let me be very clear: there is a direct line, a direct line, from that lunch counter to the Oval Office and to the fifth floor of the United States Department of Justice where the Attorney General sits. Today, as I stand before leaders who I’ve admired all my life, I fully understand that I also stand on your shoulders. So I am here to simply say ‘thank you’ as much as anything. The path I’ve been so blessed to travel was blazed by your sacrifice, by your courage, by your conviction and most of all--by your action. What seems almost easy looking back at old newsreel coverage from fifty years ago was, I know, unimaginably difficult and frightening. Despite this, SNCC and the movement it inspired persevered and succeeded.”

The appearance of Holder at the SNCC 50th highlighted a tension within the conference and within the country’s political and media establishments more widely. On one hand, nearly everyone here was part of the historic bloc that set back the GOP, unreconstructed neoliberalism and the far right. And in that sense, as well as others, Holder’s appearance was justified. On the other hand, it meant there were contending perspectives within this bloc, reaching back to when John F Kennedy tried to censor John Lewis at the 1962 March of Washington and referred to SNCC as ‘sons of bitches’ to divide them from civil rights activists who stressed a legalistic path. Even today, much media coverage likes to make a distinction between ‘the good SNCC’ that was inter-racial and stressed nonviolence and the later ‘bad SNCC’ that asked whites to leave and organize against racism in the white neighborhoods, promoted Black Power, armed self-defense and an alliance with the Black Panther Party and third world Pan-Africanist trends.

But to their credit, the organizers of the SNCC 50th maintained a welcoming unity to all trends. The three main leaders of SNCC’s latter days couldn’t be there. Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael) and James Forman had died. Jamil Al-Amin (H. Rap Brown) remains in prison, convicted of a police killing. But their families and organizations were present, and featured in the workshops. Amiri Baraka also attended, and made a powerful presentation of the Black Arts movement. Willie Ricks was unbowed as ever in his denunciations of capitalism, no matter who was in the Oval Office.

“It should never be forgotten,” said Carl Davidson, “that it was the federal government in the form of J Edgar Hoover and his COINTELPRO secret political police, that formed death squads with local police and other reactionaries, to murder some of the best of the young Black liberation fighters and otherwise sabotage the latter efforts of SNCC and the Black Panthers.”

Saturday Afternoon continued with another round of workshops: “From Cradle to Prison” on the criminalization of youth and the prison-industrial complex, “Let Us Build a New World” on youth organizing with an intergenerational dimension, and “Actions for a New World” featuring upcoming projects. The Shaw Chapel featured a talk by Dick Gregory and a special memorial session for Ella Baker, Howard Zinn and others. Saturday evening was for a “Freedom Concert,” featuring the ‘Freedom Singers’ and many other groups.

"For those of us in the generations that came after the SNCC veterans,” said Zach Robinson, a CCDS national committee member from North Carolina, “these conference workshops, especially those focused on youth, served as a school in the history and methods of grassroots organizing. We learned how movement organizers, from nearby and from afar, went into communities, became part of the day-to-day lives of community members, built organizational structures based on the democratic aspirations of those communities, marched into battle alongside them, and brought about dramatic changes.

“That means those lessons can be learned and applied today,” Robinson continued. “This was pointed out by the young organizers working in settings from urban street gangs (The Gathering), to radical environmental actions (blocking coal shipments), to anti-sweatshop solidarity organizing on college campuses, to the organizing for quality education among K-12 students. One young organizer from Durham, North Carolina spoke out from the floor, challenging participants deeply involved in various communities to seek ways to understand how their struggles are linked. It was a powerful catalyst."

The closing session Sunday morning, “Solidarity of Past , Present and Future,” tied everything together in a hopeful and inspiring way. Bob Moses was the featured speaker. Since he is very modest personally, almost to a fault, and known for powerful and pithy statements more than flowery rhetoric, this promised to be a treat. Moses was a core organizer in some of the hardest days in Mississippi, worked on the Freedom Schools there and helped found the MFDP. He later worked as a teacher in Tanzania, and most recently launched a nationwide innovative school reform movement known as ‘The Algebra Project.’

Moses delivered, in more ways than one. He started with a personal story of being called before a Mississippi judge, and being challenged with the question, “Why are you trying to register illiterates to vote?” The implication was that that judge had no idea of the self-indictment of his query: Why shouldn’t illiterates vote? Why, in this day and age, are there still illiterates? Why do you think they are illiterate anyway, and where might the blame for that condition rest and who did it serve?

Moses went on to introduce the Young People’s Project, an outgrowth of the Algebra Project. He had young people at the tables filling the gymnasium stand up and say where they were from. About a dozen cities from across the country had young people standing up. Now it all became clear why the conference was so inter-generational. In a brilliant effort, Bob Moses had organized it that way. Next he turned the discussion over to the audience. Each table was to spend 15 minutes discussing what ‘quality education’ meant to them, and then the younger people came to the podium, one after another, and reported their findings. It was typical Moses—take the spotlight off yourself, and engage the masses in speaking for themselves.

Moses then introduced Albert Sykes, a young man from Jackson, Mississippi, and a YPP ‘lead organizer.’ Sykes then spoke to the YPP’s overall aim: “We want to make a quality education for all a national constitutional right!” Not only were they engaged in school reform, they were initiating an all-out political battle for the future of young people everywhere, and relying on those where the need was greatest to take the lead.

“These young folks” said Ira Grupper, also a “March Against Fear” veteran, “had much to inform us veterans about how they are progressing today, just as we wanted to let them know our history.”

Moses summed up to effort by asking people to repeat after him all the phrases from the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution. “You don’t have to remind me about the limitations of it s meaning to the founding fathers,” he said, “just look ahead. ‘We, the People,’” he started, “but notice that it doesn’t say, ‘We, the Citizens...’ Phrase by phrase, the response from the hundreds present became louder and louder. The message was clear to all: democracy was still a revolutionary force, especially where it is denied. It is the best part of who we are, and here is a new generation accepting a torch being passed on to it for new battles down the road.

“It fits exactly with the Democracy Charter,” commented James Campbell of CCDS in South Carolina, “the new document by Jack O’Dell that’s launched as a focus for new grassroots organizing around the country.” Campbell is 85 and O’Dell is now in his nineties, making both veterans of struggles going back to the 1940s and earlier. O’Dell’s new book, Climbing Jacob’s Ladder, also includes accounts of his involvement with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, SNCC and Jesse Jackson’s ‘Rainbow Coalition’ campaigns.

Bernice Johnson Reagon gave the farewell. Her presentation was part history lesson, part sermon and mixed with song throughout. It reflected who she was, an original Freedom Singer and founder of Sweet Honey in the Rock, and she touched everyone deeply. “She showed how SNCC was part of a greater continuity,” said Zach Robinson.

As Reagon was concluding, she sang from ‘Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel!,’ about escaping from the lion’s den, she commented, “Don’t you notice that in our Gospel songs, we don’t just listen, we talk back! Our theology is about dialogue, about a vision of freedom still waiting to be born…There are still wars that need to be challenged,” she added, “war has never fixed anything.” And she closed by reminding us all that movements are never just one person’s story or one person’s solo. ”Freedom songs were sung by many voices together.”

[The article was put together from reports by James Campbell, Carl Davidson, Ira Grupper, and Zach Robinson. For more information on CCDS, the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism, got to its website at www.cc-ds.org. If you like this article, make use of the Paypal button above or at http://carldavidson.blogspot.com to lend a hand with what it cost to attend and put it together.]

--

Posted By Carl Davidson to Keep On Keepin' On... at 4/25/2010 11:13:00 AM

We’ll Never Turn Back: SNCC 50th Anniversary Celebrates Vanguard Role In Battles for Democracy

By CCDS Participants

More than 1100 people gathered at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina over the April 15-18 weekend for a 50th Anniversary gathering of the veterans of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and its close allies. SNCC was an early vanguard force in the Southern Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, as well as the Black Revolt that spread nationwide in its wake.

The reunion was an outpouring of powerful emotions, living history and inspiring visions of radical democratic change still needed in the politics of today. These were the people, now graying, who had put their bodies and their lives on the line to bring down Jim Crow segregation, gain Black political power and help end an unjust war in Vietnam. In the process, they had won major victories but were also well aware of work still to be done.

People travelled from every corner of the country to attend. They were Black and white, Asian and Chicano, and they came from all walks of life--some arrived in the bib blue jean overalls of the sharecroppers in the Deep South, while others wore dark business suits, colorful dashikis and everything in between. Most of all, their faces beamed with smiles. There were joyful and tearful embraces, many rooted in the pent-up sufferings and memories of those who had fallen, both at the time and over the years since.

"Many went to jail," said Chuck McDew, SNCC chairman from 1960 to 1963. "Many suffered. Many suffered brutalization at the hands of the law. ... While America is a different place because of SNCC, and many who have sacrificed over the years, the struggle continues."

For a gathering centered on 50-year veterans, the events in Raleigh were remarkably intergenerational. Students from Shaw and surrounding schools learned about it and decided to take part. Many of the SNCC veterans themselves brought their children and grandchildren. Most important, a large number of the SNCC activists were still engaged in organizing projects with younger generations, and these new activists attended with them.

Shaw University was important in more ways than providing a comfortable venue. It was truly a return to an historic site and source. For it was on this campus that the legendary Ella Josephine Baker and other civil rights organizers from the 1940s and 1950s called the founding conference of SNCC in 1960, inspiring and planning the events that followed.

“For all of the youthful energy and commitment to challenge and change that erupted in 1960,” said Charlie Cobb, a SNCC Field Secretary, “the reason for SNCC's existence comes down to one person—a then-57-year-old woman—Ella Baker, one of the great figures of 20th-century struggle. In a deep political sense, we are her children and our 50th anniversary conference is dedicated to her.”

The conference was structured over three-and-a-half days with large plenary gatherings alternating with a variety of choices of smaller, but still large sessions. The evenings featured cultural events and time for people to socialize and mix with old friends and new.

Highlights of the first plenaries were speeches by Julian Bond and the Rev. James Lawson. Neither minced any words about the ongoing source of the problem: the capitalist system and its structures of race, gender and class privilege. Julian Bond’s presentation was especially relevant.

"What began 50 years ago is not just history," Bond said. "It was part of a mighty movement that started many, many years before that and continues on to this day -- ordinary women, ordinary men proving they can perform extraordinary tasks in the pursuit of freedom."

“By 1965,” Bond continued, “SNCC fielded the largest staff of any civil rights organization operating in the South. It had organized nonviolent direct action against segregated facilities and voter registration projects in Alabama, Arkansas, Maryland, Missouri, Louisiana, Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Illinois, North and South Carolina, Georgia, Texas, and Mississippi.

“It had built two independent political parties and organized labor unions and agricultural co-operatives. It gave the movement for women's liberation new energy. It inspired and trained the activists who began the 'New Left.' It helped expand the limits of political debate within black America, and broadened the focus of the civil rights movement. Unlike mainstream civil rights groups, which merely sought integration of Blacks into the existing order, SNCC sought structural changes in American society itself…

“SNCC was in the vanguard in demonstrating that independent black politics could be successful. Its early attempts to use black candidates to raise issues in races where victory was unlikely expanded the political horizon. SNCC's development of independent political parties mirrored the philosophy that political form must follow function and that non-hierarchical organizations were essential to counter the growth of personality cults and self-reinforcing leadership.”

In part because of SNCC, Bond added, “Blacks have been elected to run the country, states and cities. And young blacks can go anywhere they choose. We played an important role and that role has never gotten the proper attention. But we did it because it was the right thing to do."

Bond went on to put the onus on imperialism, militarism and its wars. He had spent 20 years as a Georgia legislator, and had to beat back attempts to unseat him for his militant opposition to the Vietnam War. Later he went on to head up the NAACP, developing it in a more youth-oriented and progressive direction.

Lawson spoke later on the same theme, denouncing the ‘plantation capitalism’ that seeks a narrow financial resolution of the current economic crisis while leaving Blacks and lower-income workers generally in the lurch.

Six panels filled out the first day. Themes included the early philosophy of SNCC, how student activists integrated themselves with the rural poor and became field organizers, how SNCC grew as an organization, the societal response to SNCC, and ‘Up South’, the building of SNCC and Friends of SNCC outside of the Deep South. All of them included presenters widely known at the time—Charlie Cobb, Judy Richardson, Larry Rubin, D’Army Bailey, Tamio Wakanama, Betita Martinez, John Doar and many more.

In the panel on the “Impact of SNCC,” historian Taylor Branch spoke about the “broad democratization of politics” and “high emotion with deep thought.” Tom Hayden also declared, “We have to stand with the demonized until the demonizing ends.”

Ira Grupper, currently a CCDS national committee member from Louisville, Kentucky who earlier had served on the staff of SNCC in Georgia, as well as COFO (Council of Federated Organizations) and the MFDP (Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party) in Mississippi, also spoke during the question period. He reminded the audience that it was ordinary people, maids and janitors, who were the base, and that a joint force of the informally and formally educated was what built the movement.

But the talk of the conference was the speech by Harry Belafonte at a standing-room only lunch gathering on the second day. Now 83-years-old, the civil rights warrior and early SNCC supporter was as fiery and sharp as ever. Belafonte talked not only about the achievements of SNCC, but also the conditions of the day and the tasks undone.

"Most of what I'm hearing is about what was, and how well we did it," said Belafonte, challenging and chastising conference attendees in a hoarse, but determined voice of a wise griot. "We all know what was, and how well we did it. The question is, 'Who is talking about what is, and how badly we are doing it now?’ Yes, I'm proud that Barack Obama is president, but I find nothing that speaks to the issue of the poor. I find nothing that speaks to the issue of the disenfranchised. I find a lot of people rushing for cover anytime you criticize Barack Obama."'

Belafonte went on to praise the power and creativity of hip-hop culture, and how it had spread across the world. At the same time he denounced its treatment of women and its derailment by capitalism and the glorifications of ‘bling,’ the trappings of wealth. "Where is our voice?" Belafonte continued. "Why are we so soft? We have become too comfortable in too many ways, and we have to change." His message touched a raw nerve, but it sank in. He received a standing ovation.

One workshop that day put a spotlight on the high quality of the meetings. Entitled “More than a Hamburger,” it was referring to the original Woolworth counter sit-in and an exposition on the revolutionary implications of even the simplest battles for democracy. But the panelists present, all SNCC and Black freedom activists decades ago, also told a story in their own right in their own histories. Eleanor Holmes Norton, now a Member of Congress representing the District of Columbia and a distinguished lawyer, started as a young SNCC activist in the heady days of the Mississippi Summer Project. Gwen Patton, now a distinguished educator and theologian, came from a working-class family in Detroit to work with SNCC and SCLC in Alabama, and then headed up the National Black Antidraft and Antiwar Union.

There were more. Frank Smith, a District of Columbia Council Member, started as a SNCC field organizer in Georgia. Ed Brown, a UCC Minister, took leave from the church to engage in some the organizing work in parts of Mississippi most threatened with violence, where SNCC worker Sammy Younge had been murdered. Leah Wise, an executive director of the Southeast Regional Economic Justice Network and editor of Southern Exposure, started as a SNCC worker and went on to help the National Anti-Klan Network following the KKK killings in North Carolina in the 1970s. Doris Dozier Chrenshaw was a participant in the original Montgomery Bus Boycott sparked by Rosa Parks. Finally, Kathleen Cleaver, now with the Yale Law School, but formerly with the Black Panther Party and the New York City office of SNCC.

Any one of these individuals could have engaged hundreds of people for hours in a consciousness-raising dialogue. But this was only one workshop. Others that day, Thursday, focused on the SNCC projects in Mississippi, the projects in Alabama; where the Lowndes County Freedom Organization put up the Black Panther as its symbol and went on to win the election of a sheriff, the Border States efforts in Maryland and Northern Virginia, and the Southwest Georgia Project, where many tough battles were fought.

One remarkable cultural event later in the evening brought all this history and radical thought into one room. Entitled ‘Meet the Authors,’ it was held in a large banquet room at the Crabtree Marriot with tables lining all four walls. Here some 35 SNCC veterans displayed and autographed their latest books going into every aspect of the struggle—Bob Zellner’s ‘The Wrong Side of Murder Creek: A White Southerner in the Freedom Movement,’ John Dittmer’s ‘Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi,’ Charlie Cobb’s ‘On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Trail,’ and Betita Martinez’s ‘500 Years of Chicana Women's History,’ to name just a few. Hundreds of people stood in the room for hours, greeting old friends and discussing new ideas.

Beyond this room, the Crabtree Marriott served as a wider ‘SNCC Reunion Central’ over four days. Wander into the lobby anytime and you’d run into scenes like that of Kathleen Cleaver plugging away on her laptop while greeting old friends, and Jesse Jackson, walking through the lobby, shaking hands and greeting participants. In another corner of the lobby, there’d be Willie Ricks, the legendary firebrand of the ‘Black Power!’ slogan launched during the 250-mile ‘March Against Fear’ in 1966 Mississippi, holding forth with a circle of his friends, or Georgia State Senator Nan Grogan Orrock hugging old friends from the Southern student movement. Walk into the bar, and there’s Tom Hayden crowded with eight people around a table, having a great time solving the world’s problems. Walk further back, and there’s Kay and Walt Tillow, key organizers with the All-Unions Coalition for Single Payer, cornered with Carl Davidson, the old SDSer and current co-chair of Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism, arguing economic reforms and the path to socialism, as well as what to do about health care. And so on, night after night--bring this many politically experienced and engaged people together and there’s bound to be a high level of synergy.

The Friday workshops also presented hard choices: Depictions of the Movement in Popular Culture, Black Power/Education/Pan Africanism, The Role of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, Women Leaders and Organizers, The Black Church and the Black Struggle, Highlander, SSOC and Organizing the White Community, and SNCC in the Black Arts Movement. Any one person could only pick two.

Bob Zellner chaired the workshop on whites organizing among whites, which drew nearly 100 people. Introducing himself, Zellner said “I always tell people I was born in a police state, the state of Alabama. I also tell them my Daddy was a Bible thumping, robes-wearing Klansman, and so was my Grandpa. So that makes me born and bred in a police state and raised by fundamentalist terrorists.”

Zellner then reminded the attendees that he has never agreed with organizing whites solely as whites. He understood Blacks and other minority nationalities organizing their own forms, but he always thought it important that even if organizations were mainly made up of whites, that Blacks be included as well. “Otherwise you run into a dynamic that takes you to a bad place you don’t want to go.”

Sue Thrasher got the workshop rolling with her story of moving from being a small-town Southern farm girl to a leader in SNCC and SSOC, the Southern Student Organizing Committee. “I grew up on a farm in a rural West Tennessee county that borders North Mississippi and Alabama. My father was a farmer by choice and a carpenter by necessity. Shortly after I was born, my family moved to Oak Ridge, Tennessee where my father built housing for the defense workers who would ultimately build the atom bomb. My mother became a ‘Rosie’ of sorts, entering the work force for the first time driving an army payroll car.”

“I saw college as a way out. I was lucky. I arrived in Nashville in the fall of 1961, still a major hotbed of civil rights activities. The period from 1961 through 1966 revolutionized the shape of my life. My first tentative step to speak out on campus issues led to involvement in the local SNCC chapter, and eventually the broader southern movement. In the spring of 1964, I helped organize the founding conference of the Southern Students Organizing Committee (SSOC), an organization to grow and support fledgling civil rights activities on predominantly white campuses. I participated in Mississippi Summer as a member of the “white folks project” working in Jackson, Biloxi, and Hattiesburg. That fall, I opened SSOC’s office in Nashville and served as Executive Secretary for the next two years.”

Other panelists added to Thrasher’s account, going into descriptions of the importance of Anne Braden of SCEF and Myles Horton of the Highlander Center, where many future civil rights and labor leaders were schooled in radical methods of teaching and learning. Many stressed the ongoing importance of the Highlander Center, which is still thriving today near Knoxville, Tennessee. Zellner’s work in Mississippi, bringing together Black and white woodcutters in a single organization to fight for their rights and improve their condition, was cited as an example of what could be done.

CCDS’s Carl Davidson spoke from the floor on the current importance of the topic. In addition to working with SNCC in his SDS leadership role in the 1960s, Davidson was also a veteran of the 1966 ‘March against Fear’ in Mississippi.

“Where I work today, in the semi-rural townships of Western Pennsylvania,” Davidson commented, “if you organize at all, it’s among white workers, because that’s about all we have there. But we work closely with the labor movement, and we got a decent orientation from Richard Trumka, now head of the AFL-CIO. He told us to go door-to-door, and to meet any anti-Obama racism head-on, to tell people point blank to cast aside their prejudices or sit on them, and vote their best interests instead. That’s exactly what we did, and Trumka’s approach was picked up by union activists all across the state. Things are far from perfect, but it made a big difference in the election and in strengthening our alliances with African Americans still residing in the mill towns.”

Saturday morning’s main event took place in the sanctuary of the First Baptist Church in downtown Raleigh. Entitled ‘SNCC Veterans Introduce Their Children,’ an activity appropriate to any family gathering, and to many, SNCC was like family.

“While hundreds wept, clapped their hands and sang,” Tom Hayden reported in The Nation, “they came to the pulpit to declare themselves: Maisha Moses (Bob and Janet Moses), her brother Omo, James Forman Jr. (James Forman and Dinky Romilly), Tarik Smith (Frank and Jean Smith), Sabina Varela (Maria Varela and Lorenzo Zuniga), Bakari Sellers (Cleveland and Gwendolyn Sellers), Zora Cobb (Charles Cobb and Ann Chinn), Hollis Watkins Jr. (Hollis Watkins and Nayo Barbara Watkins), Gina Belafonte (Harry and Julie Belafonte).

“Sherry Bevel (James Bevel and Diane Nash) combined humor and compassion for her father, who was convicted of incest in 2008, released on appeal and died shortly afterward: “It would be a shame if his wit and energy was forgotten. We have had great men and women who were caught up in drug or alcohol problems, or were philandering with underage girls. But I for one don't think we should just forget Thomas Jefferson.”

She stated this turning of the tables softly, and with a sweet smile—and it brought down the house with laughter and applause.

The Saturday afternoon main session was a big deal, especially for the press. Attorney General Eric Holder was to speak, and be introduced by Congressman John Lewis, former national leader of SNCC. Lewis paid tribute to those SNCC members who were killed or beaten then in their pursuit of freedom, echoed Belafonte’s earlier concern at the conference, but also gave a rallying cry: "You've gone through the worst. You've been thrown in jail, you've been beaten. What can anyone do to you now? Make some noise.”

Lewis then turned the platform over to the Attorney General.

“On this historic day, as we celebrate the 50th Anniversary of SNCC’s beginnings,” said Holder, “I can’t help but be optimistic. And I can’t help but recall Dr. King’s prophetic reminder that "the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice." I believe that Dr. King was right, in part because of the progress I’ve witnessed during my own lifetime and the incredible healing I’ve seen.

“As a child in New York, I cheered on the Brooklyn Dodgers and their star second baseman, Jackie Robinson. As a boy, I watched Vivian Malone – a woman who later became my sister-in-law – step past George Wallace to integrate the University of Alabama. As a teenager, I felt the scope of my own dreams expand as I saw Thurgood Marshall take his historic place on our nation’s highest court. As a man, I’ve had the privilege to serve our nation’s first African-American President. And I now have the indescribable honor of leading our nation’s Justice Department as the first African-American Attorney General.

“This progress would not have, and could not have, occurred without SNCC’s work. Let me be very clear: there is a direct line, a direct line, from that lunch counter to the Oval Office and to the fifth floor of the United States Department of Justice where the Attorney General sits. Today, as I stand before leaders who I’ve admired all my life, I fully understand that I also stand on your shoulders. So I am here to simply say ‘thank you’ as much as anything. The path I’ve been so blessed to travel was blazed by your sacrifice, by your courage, by your conviction and most of all--by your action. What seems almost easy looking back at old newsreel coverage from fifty years ago was, I know, unimaginably difficult and frightening. Despite this, SNCC and the movement it inspired persevered and succeeded.”

The appearance of Holder at the SNCC 50th highlighted a tension within the conference and within the country’s political and media establishments more widely. On one hand, nearly everyone here was part of the historic bloc that set back the GOP, unreconstructed neoliberalism and the far right. And in that sense, as well as others, Holder’s appearance was justified. On the other hand, it meant there were contending perspectives within this bloc, reaching back to when John F Kennedy tried to censor John Lewis at the 1962 March of Washington and referred to SNCC as ‘sons of bitches’ to divide them from civil rights activists who stressed a legalistic path. Even today, much media coverage likes to make a distinction between ‘the good SNCC’ that was inter-racial and stressed nonviolence and the later ‘bad SNCC’ that asked whites to leave and organize against racism in the white neighborhoods, promoted Black Power, armed self-defense and an alliance with the Black Panther Party and third world Pan-Africanist trends.

But to their credit, the organizers of the SNCC 50th maintained a welcoming unity to all trends. The three main leaders of SNCC’s latter days couldn’t be there. Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael) and James Forman had died. Jamil Al-Amin (H. Rap Brown) remains in prison, convicted of a police killing. But their families and organizations were present, and featured in the workshops. Amiri Baraka also attended, and made a powerful presentation of the Black Arts movement. Willie Ricks was unbowed as ever in his denunciations of capitalism, no matter who was in the Oval Office.

“It should never be forgotten,” said Carl Davidson, “that it was the federal government in the form of J Edgar Hoover and his COINTELPRO secret political police, that formed death squads with local police and other reactionaries, to murder some of the best of the young Black liberation fighters and otherwise sabotage the latter efforts of SNCC and the Black Panthers.”

Saturday Afternoon continued with another round of workshops: “From Cradle to Prison” on the criminalization of youth and the prison-industrial complex, “Let Us Build a New World” on youth organizing with an intergenerational dimension, and “Actions for a New World” featuring upcoming projects. The Shaw Chapel featured a talk by Dick Gregory and a special memorial session for Ella Baker, Howard Zinn and others. Saturday evening was for a “Freedom Concert,” featuring the ‘Freedom Singers’ and many other groups.

"For those of us in the generations that came after the SNCC veterans,” said Zach Robinson, a CCDS national committee member from North Carolina, “these conference workshops, especially those focused on youth, served as a school in the history and methods of grassroots organizing. We learned how movement organizers, from nearby and from afar, went into communities, became part of the day-to-day lives of community members, built organizational structures based on the democratic aspirations of those communities, marched into battle alongside them, and brought about dramatic changes.

“That means those lessons can be learned and applied today,” Robinson continued. “This was pointed out by the young organizers working in settings from urban street gangs (The Gathering), to radical environmental actions (blocking coal shipments), to anti-sweatshop solidarity organizing on college campuses, to the organizing for quality education among K-12 students. One young organizer from Durham, North Carolina spoke out from the floor, challenging participants deeply involved in various communities to seek ways to understand how their struggles are linked. It was a powerful catalyst."

The closing session Sunday morning, “Solidarity of Past , Present and Future,” tied everything together in a hopeful and inspiring way. Bob Moses was the featured speaker. Since he is very modest personally, almost to a fault, and known for powerful and pithy statements more than flowery rhetoric, this promised to be a treat. Moses was a core organizer in some of the hardest days in Mississippi, worked on the Freedom Schools there and helped found the MFDP. He later worked as a teacher in Tanzania, and most recently launched a nationwide innovative school reform movement known as ‘The Algebra Project.’

Moses delivered, in more ways than one. He started with a personal story of being called before a Mississippi judge, and being challenged with the question, “Why are you trying to register illiterates to vote?” The implication was that that judge had no idea of the self-indictment of his query: Why shouldn’t illiterates vote? Why, in this day and age, are there still illiterates? Why do you think they are illiterate anyway, and where might the blame for that condition rest and who did it serve?

Moses went on to introduce the Young People’s Project, an outgrowth of the Algebra Project. He had young people at the tables filling the gymnasium stand up and say where they were from. About a dozen cities from across the country had young people standing up. Now it all became clear why the conference was so inter-generational. In a brilliant effort, Bob Moses had organized it that way. Next he turned the discussion over to the audience. Each table was to spend 15 minutes discussing what ‘quality education’ meant to them, and then the younger people came to the podium, one after another, and reported their findings. It was typical Moses—take the spotlight off yourself, and engage the masses in speaking for themselves.

Moses then introduced Albert Sykes, a young man from Jackson, Mississippi, and a YPP ‘lead organizer.’ Sykes then spoke to the YPP’s overall aim: “We want to make a quality education for all a national constitutional right!” Not only were they engaged in school reform, they were initiating an all-out political battle for the future of young people everywhere, and relying on those where the need was greatest to take the lead.

“These young folks” said Ira Grupper, also a “March Against Fear” veteran, “had much to inform us veterans about how they are progressing today, just as we wanted to let them know our history.”

Moses summed up to effort by asking people to repeat after him all the phrases from the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution. “You don’t have to remind me about the limitations of it s meaning to the founding fathers,” he said, “just look ahead. ‘We, the People,’” he started, “but notice that it doesn’t say, ‘We, the Citizens...’ Phrase by phrase, the response from the hundreds present became louder and louder. The message was clear to all: democracy was still a revolutionary force, especially where it is denied. It is the best part of who we are, and here is a new generation accepting a torch being passed on to it for new battles down the road.

“It fits exactly with the Democracy Charter,” commented James Campbell of CCDS in South Carolina, “the new document by Jack O’Dell that’s launched as a focus for new grassroots organizing around the country.” Campbell is 85 and O’Dell is now in his nineties, making both veterans of struggles going back to the 1940s and earlier. O’Dell’s new book, Climbing Jacob’s Ladder, also includes accounts of his involvement with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, SNCC and Jesse Jackson’s ‘Rainbow Coalition’ campaigns.

Bernice Johnson Reagon gave the farewell. Her presentation was part history lesson, part sermon and mixed with song throughout. It reflected who she was, an original Freedom Singer and founder of Sweet Honey in the Rock, and she touched everyone deeply. “She showed how SNCC was part of a greater continuity,” said Zach Robinson.

As Reagon was concluding, she sang from ‘Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel!,’ about escaping from the lion’s den, she commented, “Don’t you notice that in our Gospel songs, we don’t just listen, we talk back! Our theology is about dialogue, about a vision of freedom still waiting to be born…There are still wars that need to be challenged,” she added, “war has never fixed anything.” And she closed by reminding us all that movements are never just one person’s story or one person’s solo. ”Freedom songs were sung by many voices together.”

[The article was put together from reports by James Campbell, Carl Davidson, Ira Grupper, and Zach Robinson. For more information on CCDS, the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism, got to its website at www.cc-ds.org. If you like this article, make use of the Paypal button above or at http://carldavidson.blogspot.com to lend a hand with what it cost to attend and put it together.]

--

Posted By Carl Davidson to Keep On Keepin' On... at 4/25/2010 11:13:00 AM

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment