Obama's success fuels affirmative action's foes

By CHARLES BABINGTON, Associated Press Writer1 hour, 45 minutes ago

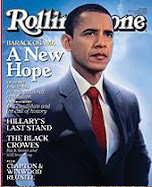

Barack Obama's political success might claim an unintended victim: affirmative action, a much-debated policy that he supports.

Already weakened by several court rulings and state referendums, affirmative action now confronts a challenge to its very reason for existing. If Americans make a black person the leading contender for president, as nationwide polls suggest, how can racial prejudice be so prevalent and potent that it justifies special efforts to place minorities in coveted jobs and schools?

"The primary rationale for affirmative action is that America is institutionally racist and institutionally sexist," said Ward Connerly, the leader of state-by-state efforts to end what he and others consider policies of reverse discrimination. "That rationale is undercut in a major way when you look at the success of Senator Clinton and Senator Obama." Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton of New York battled Obama to the end of the Democratic primary process.

Other critics of affirmative action agree. "Obama is further evidence that the great majority of Americans reject discrimination, reject prejudice," said Todd F. Gaziano, a scholar at the conservative Heritage Foundation and a member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

Not so fast, say supporters of affirmative action. Just because Barack Obama, Oprah Winfrey and other minorities have reached the top of their professions does not mean that ordinary blacks, Latinos or women are free from day-to-day biases that deny them equal access to top schools or jobs, they say.

As affirmative action's power has diminished, minority enrollment has fallen at many prominent colleges, said Gary Orfield, an authority on the subject at UCLA.

"If people get the impression from Obama's success that the racial problems of this country have been solved, that would be very sad," Orfield said. "In some ways we have moved backwards" in recent years, he said.

Wade Henderson, head of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, said, "Exceptions don't make the rule."

"By any measure, Obama and Clinton are clearly exceptional individuals," he said. "When you really examine the masses of Americans, especially women and people of color, you still find incredible disparities," which justify the continuation of affirmative action programs.

Obama, who asks voters neither to support nor oppose him on the basis of his race, has dealt gently with affirmative action. He says his two young daughters have enjoyed great advantages, and therefore should not receive special consideration because of their race.

"On the other hand," he said in an April debate, "if there's a young white person who has been working hard, struggling, and has overcome great odds, that's something that should be taken into account" by people such as college admission officers.

"So I still believe in affirmative action as a means of overcoming both historic and potentially current discrimination," Obama said. "But I think that it can't be a quota system and it can't be something that is simply applied without looking at the whole person, whether that person is black, or white, or Hispanic, male or female."

Tucker Bounds, spokesman for Republican presidential candidate John McCain, said McCain's commitment to equal opportunity for all Americans "means aggressively enforcing our nation's anti-discrimination laws."

"It also means rejecting affirmative action plans and quotas that give weight to one group of Americans at the expense of another," Bounds said. "Plans that result in quotas, where such plans have not been judicially created to remedy a specific, proven act of discrimination, only result in more discrimination."

Affirmative action, a term coined in the early 1960s, is a loosely defined set of policies meant to help rectify discrimination based on race, religion, sex or national origin. It quickly proved controversial, especially in the public arena, as some white males alleged they were losing government jobs and public university admissions to less qualified minorities and women.

The Supreme Court ruled 30 years ago that universities could use race as one factor in choosing applicants, but it banned quotas. Subsequent court decisions placed more restrictions on affirmative action, and Connerly and others launched ballot initiatives that virtually crippled it in some states.

In 1996, California voters passed Proposition 209, pushed by Connerly. It bars all government institutions from giving preferential treatment to people based on race or gender, and particularly affects college admissions and government contracts. Similar measures passed in Michigan and Washington state, and Connerly hopes to have versions on the ballots this fall in Colorado, Nebraska and Arizona.

The erosion of affirmative action is forcing colleges and other institutions to seek new ways of pursuing diversity, with mixed results.

"What had been a national policy is being dismantled, state by state," University of Washington President Mark A. Emmert wrote in the Christian Science Monitor last year. He said his campus has learned that it still can "ensure diversity and access to higher education, particularly by taking socio-economic factors into account."

While Emmert laments the erosion of affirmative action, others say it is overdue. It's great if Obama's success hastens the process, they say, but previous achievements by blacks in business, government, entertainment and other fields already have undermined the argument that racial discrimination is rampant.

Defenders of affirmative action cite continuing disparities between blacks and whites in areas such as income, education achievement, health care and incarceration rates. These disparities, however, "have roots in problems that are not addressed by affirmative action," said Abigail Thernstrom, a Manhattan Institute senior fellow and vice chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

They are complex, deep-seated factors that put many minority children behind their peers as early as kindergarten, she said. In confronting such challenges, she said, "racial preferences don't solve anything."

To some extent, Obama agrees that affirmative action is poorly suited to address such problems. But it still is needed, he says.

"Affirmative action is an important tool, although a limited tool," Obama told National Public Radio last year.

"I say limited simply because a large portion of our young people right now never even benefit from affirmative action because they're not graduating from high school," he said. "And unless we do a better job with early childhood education, fixing crumbling schools, investing to make sure that we've got an excellent teacher in front of every classroom, and then making college affordable, we're not even going to reach the point where our children can benefit from affirmative action."

No comments:

Post a Comment