Friday, May 2, 2008

On Liberation Theology: A Noted Theologian

Susan Brooks Thistlethwaite

Rev. Wright and the Religious Right

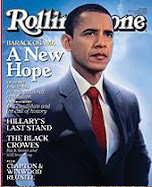

Senator Obama has built his campaign on the premise that Americans can reach out to one another across historic divides and regain national strength and purpose after decades of “divide and conquer” politics. It has become clear to me this week, and I think probably to many Americans, that this is who he really is and what he most deeply believes. It plainly pained him terribly to separate himself and his campaign so decisively from the statements of Rev. Wright, but he had to do it because their views of the future are so different.

Beyond the media hype, there are some real differences at stake in this controversy about how we move forward as Americans. As the dust settles, I think we can delve more deeply into these differences and make real choices.

There are two main ways people can effect social change, strategies of continuity and strategies of discontinuity. Each of these strategies has its strengths and each has its weaknesses. We need to ask ourselves as a nation, what do we need now? That does not mean, however, that one strategy solves all our problems and the other strategy is the problem. History doesn’t line up so neatly.

Context and historical moments matter and they matter profoundly in religion as well as in politics. There has been frequent mention of the term “liberation theology” in the press without much evidence of any real understanding of the content. This is an area where I have some expertise since I have taught liberation theology for nearly three decades and have co-authored and edited a textbook that is widely used to teach liberation theology. If you are interested in doing more reading on this subject, the textbook is called Lift Every Voice: Constructing Christian Theologies from the Underside.

What matters in a liberation approach to theology is that you take your context seriously, you look at what is really happening in the historical moment in which you find yourself and you try to find where God is working in the world on behalf of peace and justice and you align yourself as best you can with, as Dr. King said, “the arc of history” that is bending toward justice.

There are profound cultural, racial, gender and generational differences in how we approach these questions of history and justice. Liberation theology was first articulated in Latin America by Catholic priests in response to the profound poverty of the majority of their people and the concentrations of wealth and power in the hands of a very few. These Catholic priests looked at the economies of their countries through the gospel of Jesus Christ and his annunciation of his ministry as “good news to the poor”. The analysis they used was rich versus poor and it is not hard to see why they would see their historical context in such stark and oppositional ways.

The weakness of this first generation of liberation theology is that it can lead its adherents to see everything from the perspective of “oppressor vs. oppressed” and this in turn leads to an “us vs. them” approach that can make coalition building very difficult. It also leads the “good vs. evil” frame where all the good is on MY side, and all the evil is all the fault of the OTHER.

Women theologians were the first to point out to these Latin American male priests that they were blinded, in their theological method, to their own oppressive views of women. Yet, North American women did adopt some forms of liberation theology in the early years of the women’s rights movement in the U.S.

As liberation theology has spread around the world and been in dialogue with many different cultures and historical moments, it has changed and grown. It remains a powerful tool for a religious critique of injustice.

Rev. Wright’s views appear deeply formed by the oppressions of race that have been so evident in American history. The weakness of his approach, especially evident in his generation, is getting locked into the “good vs. evil” frame. If you emphasize that part of the dynamic too much, then it makes overcoming divisions much more difficult.

Oddly enough, it has been my observation that Senator Hillary Clinton also works out of a classical liberation approach of “good vs. evil”. An example of this would be the Clinton surrogate who called Governor Richardson a long-time Clinton friend, “Judas” for deciding to support Obama. “Judas” is a biblical figure who is, of course, very evil. This good vs. evil approach for Hillary (and through those who speak for her) may come from her background in that early generation of the women’s movement and/or from her and her husband’s political battles with the political and religious right. The political and the religious right also have a “good vs. evil” frame and it is understandable how struggling with them all these years would have caused the Clintons to mirror that right back.

I am having trouble getting a read on where Senator McCain falls along this continuum; theologically speaking, he seems to be more like John Kerry and Kerry’s belief that his faith was private. His strategy for social change is not evident to me, though perhaps that will emerge over time.

The political and I think the religious approach that defines Senator Obama is one that represents generational change, but it has its roots in the strategies of continuity of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. King used the words of the American founders as the basis for his demand that all Americans, black and white, get an equal share of the American dream. I think that Obama has built on that and holds a progressive social and religious view that sees the world and the work of social justice as more complex than “we vs. they” and he clearly works out of a progressive strategy of continuity. This is also, as I said, a generational shift as people increasingly try to come to grips with the complex dynamics of social change in an increasingly complicated world.

The strength of a progressive view of the world is its capacity to reach out across historic divides and build new coalitions. The risk in a progressive strategy is that deeply entrenched wrongs can be overlooked or minimized unless great care is taken to deeply explore the roots of the problems we wish to address with our transformative change strategies.

Beyond the media driven controversy, the question you and I have to ask ourselves is what do we need now? I am increasingly attracted myself to the progressive perspective and building new coalitions because I think we have gone too far in the direction of “we vs. they” and “good vs. evil.” The last decades in this country have produced almost nothing but division and this has resulted in political paralysis so that nothing that needs changing is really getting changed. I think this whole recent controversy illustrates how easily we as a country can get locked into polarizing division and I’m tired of that.

Posted by Susan Brooks Thistlethwaite on May 2, 2008 6:12 AM

More Posts About: Mainline Protestant

Rev. Susan Brooks Thistlethwaite is president of Chicago Theological Seminary and senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. She has been a professor of theology at the seminary for 20 years and director of its graduate degree center for five years. Her area of expertise is contextual theologies of liberation, specializing in issues of violence and violation. An ordained minister of the United Church of Christ since 1974, the “On Faith” panelist is the author or editor of thirteen books and has been a translator for two translations of the Bible. Her works include Casting Stones: Prostitution and Liberation in Asia and the United States (1996) and The New Testament and Psalms: An Inclusive Translation (1995). Since the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, Thistlethwaite has been working diligently to promote peace, including a presentation at the U.S. Institute of Peace, which appears in one of their special reports. Most recently she edited and contributed to Adam, Eve and the Genome: Theology in Dialogue with the Human Genome Project (2003). Close. Susan Brooks Thistlethwaite

She has been a professor of theology at the seminary for 20 years and director of its graduate degree center for five years. Her area of expertise is contextual theologies of liberation, specializing in issues of violence and violation.

Rev. Wright and the Religious Right

Senator Obama has built his campaign on the premise that Americans can reach out to one another across historic divides and regain national strength and purpose after decades of “divide and conquer” politics. It has become clear to me this week, and I think probably to many Americans, that this is who he really is and what he most deeply believes. It plainly pained him terribly to separate himself and his campaign so decisively from the statements of Rev. Wright, but he had to do it because their views of the future are so different.

Beyond the media hype, there are some real differences at stake in this controversy about how we move forward as Americans. As the dust settles, I think we can delve more deeply into these differences and make real choices.

There are two main ways people can effect social change, strategies of continuity and strategies of discontinuity. Each of these strategies has its strengths and each has its weaknesses. We need to ask ourselves as a nation, what do we need now? That does not mean, however, that one strategy solves all our problems and the other strategy is the problem. History doesn’t line up so neatly.

Context and historical moments matter and they matter profoundly in religion as well as in politics. There has been frequent mention of the term “liberation theology” in the press without much evidence of any real understanding of the content. This is an area where I have some expertise since I have taught liberation theology for nearly three decades and have co-authored and edited a textbook that is widely used to teach liberation theology. If you are interested in doing more reading on this subject, the textbook is called Lift Every Voice: Constructing Christian Theologies from the Underside.

What matters in a liberation approach to theology is that you take your context seriously, you look at what is really happening in the historical moment in which you find yourself and you try to find where God is working in the world on behalf of peace and justice and you align yourself as best you can with, as Dr. King said, “the arc of history” that is bending toward justice.

There are profound cultural, racial, gender and generational differences in how we approach these questions of history and justice. Liberation theology was first articulated in Latin America by Catholic priests in response to the profound poverty of the majority of their people and the concentrations of wealth and power in the hands of a very few. These Catholic priests looked at the economies of their countries through the gospel of Jesus Christ and his annunciation of his ministry as “good news to the poor”. The analysis they used was rich versus poor and it is not hard to see why they would see their historical context in such stark and oppositional ways.

The weakness of this first generation of liberation theology is that it can lead its adherents to see everything from the perspective of “oppressor vs. oppressed” and this in turn leads to an “us vs. them” approach that can make coalition building very difficult. It also leads the “good vs. evil” frame where all the good is on MY side, and all the evil is all the fault of the OTHER.

Women theologians were the first to point out to these Latin American male priests that they were blinded, in their theological method, to their own oppressive views of women. Yet, North American women did adopt some forms of liberation theology in the early years of the women’s rights movement in the U.S.

As liberation theology has spread around the world and been in dialogue with many different cultures and historical moments, it has changed and grown. It remains a powerful tool for a religious critique of injustice.

Rev. Wright’s views appear deeply formed by the oppressions of race that have been so evident in American history. The weakness of his approach, especially evident in his generation, is getting locked into the “good vs. evil” frame. If you emphasize that part of the dynamic too much, then it makes overcoming divisions much more difficult.

Oddly enough, it has been my observation that Senator Hillary Clinton also works out of a classical liberation approach of “good vs. evil”. An example of this would be the Clinton surrogate who called Governor Richardson a long-time Clinton friend, “Judas” for deciding to support Obama. “Judas” is a biblical figure who is, of course, very evil. This good vs. evil approach for Hillary (and through those who speak for her) may come from her background in that early generation of the women’s movement and/or from her and her husband’s political battles with the political and religious right. The political and the religious right also have a “good vs. evil” frame and it is understandable how struggling with them all these years would have caused the Clintons to mirror that right back.

I am having trouble getting a read on where Senator McCain falls along this continuum; theologically speaking, he seems to be more like John Kerry and Kerry’s belief that his faith was private. His strategy for social change is not evident to me, though perhaps that will emerge over time.

The political and I think the religious approach that defines Senator Obama is one that represents generational change, but it has its roots in the strategies of continuity of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. King used the words of the American founders as the basis for his demand that all Americans, black and white, get an equal share of the American dream. I think that Obama has built on that and holds a progressive social and religious view that sees the world and the work of social justice as more complex than “we vs. they” and he clearly works out of a progressive strategy of continuity. This is also, as I said, a generational shift as people increasingly try to come to grips with the complex dynamics of social change in an increasingly complicated world.

The strength of a progressive view of the world is its capacity to reach out across historic divides and build new coalitions. The risk in a progressive strategy is that deeply entrenched wrongs can be overlooked or minimized unless great care is taken to deeply explore the roots of the problems we wish to address with our transformative change strategies.

Beyond the media driven controversy, the question you and I have to ask ourselves is what do we need now? I am increasingly attracted myself to the progressive perspective and building new coalitions because I think we have gone too far in the direction of “we vs. they” and “good vs. evil.” The last decades in this country have produced almost nothing but division and this has resulted in political paralysis so that nothing that needs changing is really getting changed. I think this whole recent controversy illustrates how easily we as a country can get locked into polarizing division and I’m tired of that.

Posted by Susan Brooks Thistlethwaite on May 2, 2008 6:12 AM

More Posts About: Mainline Protestant

Rev. Susan Brooks Thistlethwaite is president of Chicago Theological Seminary and senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. She has been a professor of theology at the seminary for 20 years and director of its graduate degree center for five years. Her area of expertise is contextual theologies of liberation, specializing in issues of violence and violation. An ordained minister of the United Church of Christ since 1974, the “On Faith” panelist is the author or editor of thirteen books and has been a translator for two translations of the Bible. Her works include Casting Stones: Prostitution and Liberation in Asia and the United States (1996) and The New Testament and Psalms: An Inclusive Translation (1995). Since the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, Thistlethwaite has been working diligently to promote peace, including a presentation at the U.S. Institute of Peace, which appears in one of their special reports. Most recently she edited and contributed to Adam, Eve and the Genome: Theology in Dialogue with the Human Genome Project (2003). Close. Susan Brooks Thistlethwaite

She has been a professor of theology at the seminary for 20 years and director of its graduate degree center for five years. Her area of expertise is contextual theologies of liberation, specializing in issues of violence and violation.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment