Forgive the length of the piece but it is an important analysis for understanding today's politics.

RGN

Opinion

The Fall of ConservatismMonday 26 May 2008

by: George Packer, The New Yorker

From Nixon until now, conservatism has served to dominate US political discourse. (Photo: ABC News)

Have the Republicans run out of ideas?

The era of American politics that has been dying before our eyes was born in 1966. That January, a twenty-seven-year-old editorial writer for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat named Patrick Buchanan went to work for Richard Nixon, who was just beginning the most improbable political comeback in American history. Having served as Vice-President in the Eisenhower Administration, Nixon had lost the Presidency by a whisker to John F. Kennedy, in 1960, and had been humiliated in a 1962 bid for the California governorship. But he saw that he could propel himself back to power on the strength of a new feeling among Americans who, appalled by the chaos of the cities, the moral heedlessness of the young, and the insults to national pride in Vietnam, were ready to blame it all on the liberalism of President Lyndon B. Johnson. Right-wing populism was bubbling up from below; it needed to be guided by a leader who understood its resentments because he felt them, too.

"From Day One, Nixon and I talked about creating a new majority," Buchanan told me recently, sitting in the library of his Greek-revival house in McLean, Virginia, on a secluded lane bordering the fenced grounds of the Central Intelligence Agency. "What we talked about, basically, was shearing off huge segments of F.D.R.'s New Deal coalition, which L.B.J. had held together: Northern Catholic ethnics and Southern Protestant conservatives - what we called the Daley-Rizzo Democrats in the North and, frankly, the Wallace Democrats in the South." Buchanan grew up in Washington, D.C., among the first group - men like his father, an accountant and a father of nine, who had supported Roosevelt but also revered Joseph McCarthy. The Southerners were the kind of men whom Nixon whipped into a frenzy one night in the fall of 1966, at the Wade Hampton Hotel, in Columbia, South Carolina. Nixon, who was then a partner in a New York law firm, had travelled there with Buchanan on behalf of Republican congressional candidates. Buchanan recalls that the room was full of sweat, cigar smoke, and rage; the rhetoric, which was about patriotism and law and order, "burned the paint off the walls." As they left the hotel, Nixon said, "This is the future of this Party, right here in the South."

Nixon and Buchanan visited thirty-five states that fall, and in November the Republicans won a midterm landslide. It was the end of Lyndon Johnson's Great Society, the beginning of his fall from power. In order to seize the Presidency in 1968, Nixon had to live down his history of nasty politicking, and he ran that year as a uniter. But his Administration adopted an undercover strategy for building a Republican majority, working to create the impression that there were two Americas: the quiet, ordinary, patriotic, religious, law-abiding Many, and the noisy, élitist, amoral, disorderly, condescending Few.

This strategy was put into action near the end of Nixon's first year in office, when antiwar demonstrators were becoming a disruptive presence in Washington. Buchanan recalls urging Nixon, "We've got to use the siege gun of the Presidency, and go right after these guys." On November 3, 1969, Nixon went on national television to speak about the need to avoid a shameful defeat in Vietnam. Looking benignly into the camera, he concluded, "And so tonight - to you, the great silent majority of Americans - I ask for your support." It was the most successful speech of his Presidency. Newscasters criticized him for being divisive and for offering no new vision on Vietnam, but tens of thousands of telegrams and letters expressing approval poured into the White House. It was Nixon's particular political genius to rouse simultaneously the contempt of the bien-pensants and the admiration of those who felt the sting of that contempt in their own lives.

Buchanan urged Nixon to enlist his Vice-President, Spiro Agnew, in a battle against the press. In November, Nixon sent Agnew - despised as dull-witted by the media - on the road, where he denounced "this small and unelected élite" of editors, anchormen, and analysts. Buchanan recalls watching a broadcast of one such speech - which he had written for Agnew - on a television in his White House office. Joining him was his colleague Kevin Phillips, who had just published "The Emerging Republican Majority," which marshalled electoral data to support a prophecy that Sun Belt conservatism - like Jacksonian Democracy, Republican industrialism, and New Deal liberalism - would dominate American politics for the next thirty-two or thirty-six years. (As it turns out, Phillips was slightly too modest.) When Agnew finished his diatribe, Phillips said two words: "Positive polarization."

Polarization is the theme of Rick Perlstein's new narrative history "Nixonland" (Scribners), which covers the years between two electoral landslides: Barry Goldwater's defeat in 1964 and George McGovern's in 1972. During that time, Nixon figured out that he could succeed politically "by using the angers, anxieties, and resentments produced by the cultural chaos of the 1960s," which were also his own. In Perlstein's terms, America in the sixties was divided, like the Sneetches on Dr. Seuss's beaches, into two social clubs: the Franklins, who were the in-crowd at Nixon's alma mater, Whittier College; and the Orthogonians, a rival group founded by Nixon after the Franklins rejected him, made up of "the strivers, those not to the manor born, the commuter students like him. He persuaded his fellows that reveling in one's unpolish was a nobility of its own." Orthogonians deeply resented Franklins, which, as Perlstein sees it, explains just about everything that happened between 1964 and 1972: Nixon resented the Kennedys and clawed his way back to power; construction workers resented John Lindsay and voted conservative; National Guardsmen resented student protesters and opened fire on them. Perlstein sustains these categories throughout the book, without quite noticing that his scheme breaks down under the pressure of his central historical insight - "America was engulfed in a pitched battle between the forces of darkness and the forces of light. The only thing was: Americans disagreed radically over which side was which." In other words, by 1972 there were hardly any Franklins left - only former Franklins who had thrown off their dinner jackets, picked up a weapon, and joined the brawl. The sixties, which began in liberal consensus over the Cold War and civil rights, became a struggle between two apocalyptic politics that each saw the other as hellbent on the country's annihilation. The result was violence like nothing the country had seen since the Civil War, and Perlstein emphasizes that bombings, assaults, and murders committed by segregationists, hardhats, and vigilantes on the right were at least as numerous as those by radical students and black militants on the left. Nixon claimed to speak on behalf of "the nonshouters, the nondemonstrators," but the cigar smokers in that South Carolina hotel were intoxicated with hate.

Nixon was coldly mixing and pouring volatile passions. Although he was careful to renounce the extreme fringe of Birchites and racists, his means to power eventually became the end. Buchanan gave me a copy of a seven-page confidential memorandum - "A little raw for today," he warned - that he had written for Nixon in 1971, under the heading "Dividing the Democrats." Drawn up with an acute understanding of the fragilities and fault lines in "the Old Roosevelt Coalition," it recommended that the White House "exacerbate the ideological division" between the Old and New Left by praising Democrats who supported any of Nixon's policies; highlight "the elitism and quasi-anti-Americanism of the National Democratic Party"; nominate for the Supreme Court a Southern strict constructionist who would divide Democrats regionally; use abortion and parochial-school aid to deepen the split between Catholics and social liberals; elicit white working-class support with tax relief and denunciations of welfare. Finally, the memo recommended exploiting racial tensions among Democrats. "Bumper stickers calling for black Presidential and especially Vice-Presidential candidates should be spread out in the ghettoes of the country," Buchanan wrote. "We should do what is within our power to have a black nominated for Number Two, at least at the Democratic National Convention." Such gambits, he added, could "cut the Democratic Party and country in half; my view is that we would have far the larger half."

The Nixon White House didn't enact all of these recommendations, but it would be hard to find a more succinct and unapologetic blueprint for Republican success in the conservative era. "Positive polarization" helped the Republicans win one election after another - and insured that American politics would be an ugly, unredeemed business for decades to come.

Perlstein argues that the politics of "Nixonland" will endure for at least another generation. On his final page, he writes, "Do Americans not hate each other enough to fantasize about killing one another, in cold blood, over political and cultural disagreements? It would be hard to argue they do not." Yet the polarization of America, which we now call the "culture wars," has been dissipating for a long time. Because we can't anticipate what ideas and language will dominate the next cycle of American politics, the previous era's key words - "élite," "mainstream," "real," "values," "patriotic," "snob," "liberal" - seem as potent as ever. Indeed, they have shown up in the current campaign: North Carolina and Mississippi Republicans have produced ads linking local Democrats to Jeremiah Wright, Barack Obama's controversial former pastor. The right-wing group Citizens United has said that it will run ads portraying Obama as yet another "limousine liberal." But these are the spasms of nerve endings in an organism that's brain-dead. Among Republicans, there is no energy, no fresh thinking, no ability to capture the concerns and feelings of millions of people. In the past two months, Democratic targets of polarization attacks have won three special congressional elections, in solidly Republican districts in Illinois, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Political tactics have a way of outliving their ability to respond to the felt needs and aspirations of the electorate: Democrats continued to accuse Republicans of being like Herbert Hoover well into the nineteen-seventies; Republicans will no doubt accuse Democrats of being out of touch with real Americans long after George W. Bush retires to Crawford, Texas. But the 2006 and 2008 elections are the hinge on which America is entering a new political era.

This will be true whether or not John McCain, the presumptive Republican nominee, wins in November. He and his likely Democratic opponent, Barack Obama, "both embody a post-polarized, or anti-polarized, style of politics," the Times columnist David Brooks told me. "McCain, crucially, missed the sixties, and in some ways he's a pre-sixties figure. He and Obama don't resonate with the sixties at all." The fact that the least conservative, least divisive Republican in the 2008 race is the last one standing - despite being despised by significant voices on the right - shows how little life is left in the movement that Goldwater began, Nixon brought into power, Ronald Reagan gave mass appeal, Newt Gingrich radicalized, Tom DeLay criminalized, and Bush allowed to break into pieces. "The fact that there was no conventional, establishment, old-style conservative candidate was not an accident," Brooks said. "Mitt Romney pretended to be one for a while, but he wasn't. Rudy Giuliani sort of pretended, but he wasn't. McCain is certainly not. It's not only a lack of political talent - there's just no driving force, and it will soften up normal Republicans for change."

On May 6th, Newt Gingrich posted a message, "My Plea to Republicans: It's Time for Real Change to Avoid Real Disaster," on the Web site of the conservative magazine Human Events. The former House Speaker warned, "The Republican brand has been so badly damaged that if Republicans try to run an anti-Obama, anti-Reverend Wright, or (if Senator Clinton wins) anti-Clinton campaign, they are simply going to fail." Gingrich offered nine suggestions for restoring the Republican "brand" - among them "Overhaul the census and cut its budget radically" and "Implement a space-based, G.P.S.-style air-traffic control system" - which read like a wonkish parody of the Contract with America. By the next morning, the post had received almost three hundred comments, almost all predicting a long Republican winter.

Yuval Levin, a former Bush White House official, who is now a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, agrees with Gingrich's diagnosis. "There's an intellectual fatigue, even if it hasn't yet been made clear by defeat at the polls," he said. "The conservative idea factory is not producing as it did. You hear it from everybody, but nobody agrees what to do about it."

Pat Buchanan was less polite, paraphrasing the social critic Eric Hoffer: "Every great cause begins as a movement, becomes a business, and eventually degenerates into a racket."

Only a few years ago, on the night of Bush's victory in 2004, the conservative movement seemed indomitable. In fact, it was rapidly falling apart. Conservatives knew how to win elections; however, they turned out not to be very interested in governing. Throughout the decades since Nixon, conservatism has retained the essentially negative character of an insurgent movement.

Nixon himself was more interested in global grand strategy and partisan politics than in any conservative policy agenda. By today's standards, his achievements in office look like those of a moderate liberal: he eased the tensions of the Cold War, expanded the welfare state, and supported affirmative action (albeit in ways calculated to split the Democrats). "L.B.J. built the foundation and the first floor of the Great Society," Buchanan said. "We built the skyscraper. Nixon was not a Reaganite conservative."

Even Reagan, the Moses of the conservative movement, was more ideological in his rhetoric than in his governance. Conservatives have canonized him for cutting taxes and regulation, moving the courts to the right, and helping to vanquish the Soviet empire. But he proved less dogmatic than most of his opponents and some of his followers expected, especially on ending the Cold War. Reagan emphasized the first word in "positive polarization," turning the Nixon playbook into a kind of national celebration. Like F.D.R., he dominated an era by reconciling opposites through force of personality: just as Roosevelt the patrician became the tribune of the people, Reagan turned conservatism into a forward-looking, optimistic ideology. "We started in 1980 and played addition," Ed Rollins, Reagan's political director, recalls. " 'Let's go out and get Democrats.' We attracted a great many young people to the Party. Reagan made them feel good about the country again. After the '84 election, we did polling - Why did you vote for Reagan? They said, 'He's a winner.' "

The Princeton historian Sean Wilentz, in his new book, "The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974-2008" (Harper), argues that Reagan "learned how to seize and keep control of the terms of public debate." On taxes, race, government spending, national security, crime, welfare, and "traditional values," he made mainstream what had been the positions of the right-wing fringe, and he kept Democrats on the defensive. He also brought a generation of doctrinaire conservatives into the bureaucracy and the courts, making appointments based on ideological tests that only a genuine movement leader would impose. The rightward turn of the judiciary will probably be the most lasting achievement of Reagan and his movement.

In retrospect, the Reagan Presidency was the high-water mark of conservatism. "In some respects, the conservative movement was a victim of success," Wilentz concludes. "With the Soviet Union dissolved, inflation reduced to virtually negligible levels, and the top tax rate cut to nearly half of what it was in 1980, all of Ronald Reagan's major stated goals when he took office had been achieved, leaving perplexed and fractious conservatives to fight over where they might now lead the country." Wilentz omits one important failure. According to Buchanan, who was the White House communications director in Reagan's second term, the President once told his barber, Milton Pitts, "You know, Milt, I came here to do five things, and four out of five ain't bad." He had succeeded in lowering taxes, raising morale, increasing defense spending, and facing down the Soviet Union; but he had failed to limit the size of government, which, besides anti-Communism, was the abiding passion of Reagan's political career and of the conservative movement. He didn't come close to achieving it and didn't try very hard, recognizing early that the public would be happy to have its taxes cut as long as its programs weren't touched. And Reagan was a poor steward of the unglamorous but necessary operations of the state. Wilentz notes that he presided over a period of corruption and favoritism, encouraging hostility toward government agencies and "a general disregard for oversight safeguards as among the evils of 'big government.' " In this, and in a notorious attempt to expand executive power outside the Constitution - the Iran-Contra affair - Reagan's Presidency presaged that of George W. Bush.

After Reagan and the end of the Cold War, conservatism lost the ties that had bound together its disparate factions - libertarians, evangelicals, neoconservatives, Wall Street, working-class traditionalists. Without the Gipper and the Evil Empire, what was the organizing principle? In 1994, the conservative journalist David Frum surveyed the landscape and published a book called "Dead Right." Reagan, he wrote, had offered his "Morning in America" vision, and the public had rewarded him enormously, but in failing to reduce government he had allowed the welfare state to continue infantilizing the public, weakening its moral fibre. That November, Republicans swept to power in Congress and imagined that they had been deputized by the voters to distill conservatism into its purest essence. Newt Gingrich declared, "On those things which are at the core of our philosophy and on those things where we believe we represent the vast majority of Americans, there will be no compromise." Instead of just limiting government, the Gingrich revolutionaries set out to disable it. Although the legislative reins were in their hands, these Republicans could find no governmental projects to organize their energy around. David Brooks said, "The only thing that held the coalition together was hostility to government." When the Times Magazine asked William Kristol what ideas he was for - in early 1995, high noon of the Gingrich Revolution - Kristol could think to mention only school choice and "shaping the culture."

At the end of that year, when the radical conservatives in the Gingrich Congress shut down the federal government, they learned that the American public was genuinely attached to the modern state. "An anti-government philosophy turned out to be politically unpopular and fundamentally un-American," Brooks said. "People want something melioristic, they want government to do things."

Instead of governing, the Republican majority in Congress - along with right-wing authors, journalists, talk-radio personalities, think tanks, and foundations - surrendered to the negative strain of modern conservatism. As political strategy, this strain went back to the Nixon era, but its philosophical roots were older and deeper. It extended back to William F. Buckley, Jr.,'s mission statement, in the inaugural issue of National Review, in 1955, that the new magazine "stands athwart history, yelling Stop"; and to Goldwater's seminal 1960 book, "The Conscience of a Conservative," in which he wrote, "I have little interest in streamlining government or in making it more efficient, for I mean to reduce its size. I do not undertake to promote welfare, for I propose to extend freedom. My aim is not to pass laws, but to repeal them. It is not to inaugurate new programs, but to cancel old ones." By the end of the century, a movement inspired by sophisticated works such as Russell Kirk's 1953 "The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot" churned out degenerate descendants with titles like "How to Talk to a Liberal (If You Must)." Shortly after engineering President Bill Clinton's impeachment on a narrow party-line basis, Gingrich was gone.

Though conservatives were not much interested in governing, they understood the art of politics. They hadn't made much of a dent in the bureaucracy, and they had done nothing to provide universal health-care coverage or arrest growing economic inequality, but they had created a political culture that was inhospitable to welfare, to an indulgent view of criminals, to high rates of taxation. They had controlled the language and moved the political parameters to the right. Back in November, 1967, Buckley wrote in an essay on Ronald Reagan, "They say that his accomplishments are few, that it is only the rhetoric that is conservative. But the rhetoric is the principal thing. It precedes all action. All thoughtful action."

In 2000, George W. Bush presented himself as Reagan's heir, but he didn't come into office with Reagan's ideological commitments or his public-policy goals. According to Frum, who worked as a White House speechwriter during Bush's first two years, Bush couldn't have won if he'd run as a real conservative, because the country was already moving in a new direction. Bush's goals, like Nixon's, were political. Nixon had set out to expand the Republican vote; Bush wanted to keep it from contracting. At his first meeting with Frum and other speechwriters, Bush declared, "I want to change the Party" - to soften its hard edge, and make the Party more hospitable to Hispanics. "It was all about positioning," Frum said, "not about confronting a new generation of problems." Frum wasn't happy; although he suspected that Bush might be right, he wanted him to govern along hard-line conservative principles.

The phrase that signalled Bush's approach was "compassionate conservatism," but it never amounted to a policy program. Within hours of the Supreme Court decision that ended the disputed Florida recount, Dick Cheney met with a group of moderate Republican senators, including Lincoln Chafee, of Rhode Island. According to Chafee's new book, "Against the Tide: How a Compliant Congress Empowered a Reckless President" (Thomas Dunne), the Vice-President-elect gave the new order of battle: "We would seek confrontation on every front... . The new Administration would divide Americans into red and blue, and divide nations into those who stand with us or against us." Cheney's combative instincts and belief in an unfettered and secretive executive proved far more influential at the White House than Bush's campaign promise to be "a uniter, not a divider." Cheney behaved as if, notwithstanding the loss of the popular vote, conservative Republican domination could continue by sheer force of will. On domestic policy, the Administration made tax cuts and privatization its highest priority; and its conduct of the war on terror broke with sixty years of relatively bipartisan and multilateralist foreign policy.

The Administration's political operatives were moving in the same direction. The Republican strategist Matthew Dowd studied the 2000 results and concluded that the proportion of swing voters in America had declined from twenty-two to seven per cent over the previous two decades, which meant that mobilizing the Party's base would be more important in 2004 than attracting independents. The strategist Karl Rove's polarizing political tactics (which brought a new level of demographic sophistication to the old formula) buried any hope of a centrist Presidency before Bush's first term was half finished.

Ed Rollins said, "Rove knew his voters, he stuck to the message with consistency, he drove that base hard - and there's nothing left of it. Today, if you're not rich or Southern or born again, the chances of your being a Republican are not great." As long as Bush and his party kept winning elections, however slim the margins, Rove's declared ambition to create a "permanent majority" seemed like the vision of a tactical genius. But it was built on two illusions: that the conservative era would stretch on indefinitely, and that politics matters more than governing. The first illusion defied history; the second was blown up in Iraq and drowned in New Orleans. David Brooks argues that these disasters discredited both neo- and compassionate conservatism in the eyes of many Republicans. "You've got to learn from the failures," Brooks told me. "But Republicans have rejected the entire attempt. For example, after Katrina, House Republicans wanted nothing to do with New Orleans. They were, like, 'We don't care about those people.' "

In its final year, the Bush Administration is seen by many conservatives (along with seventy per cent of Americans) to be a failure. Among true believers, there are two explanations of why this happened and what it portends. One is the purist version: Bush expanded the size of government and created huge deficits; allowed Republicans in Congress to fatten lobbyists and stuff budgets full of earmarks; tried to foist democracy on a Muslim country; failed to secure the border; and thus won the justified wrath of the American people. This account - shared by Pat Buchanan, the columnist George F. Will, and many Republicans in Congress - has the appeal of asking relatively little of conservatives. They need only to repent of their sins, rid themselves of the neoconservatives who had agitated for the Iraq invasion, and return to first principles. Buchanan said, "The conservatives need to, in Maoist terms, go back to Yenan."

The second version - call it reformist - is more painful, because it's based on the recognition that, though Bush's fatal incompetence and Rove's shortsighted tactics hastened the conservative movement's demise, they didn't cause it. In this view, conservatism has a more serious problem than self-betrayal: a doctrinaire failure to adapt to new circumstances, new problems. Instead of heading back to Yenan to regroup, conservatives will have to spend some years or even decades wandering across a bleak political landscape of losing campaigns and rebranding efforts and earnest policy retreats, much as liberals did after 1968, before they can hope to reëstablish dominance.

Recently, I spoke with a number of conservatives about their movement. The younger ones - say, those under fifty - uniformly subscribe to the reformist version. They are in a state of glowing revulsion at the condition of their political party. Most of them predicted that Republicans will lose the Presidency this year and suffer a rout in Congress. They seemed to feel that these losses would be deserved, and suggested that, if the party wins, it will be - in the words of Rich Lowry, the thirty-nine-year-old editor of National Review - "by default."

On April 4th, a rainy day in New York, I attended Buckley's memorial Mass at St. Patrick's Cathedral with some two thousand people, an unusually large number of them women in hats and men in bow ties. George W. Rutler, the presiding priest, declared that Buckley's words helped "crack the walls of an evil empire." Secular humanism, he said, "builds little hells for man on earth... . Communism was worse than a social tyranny because it was a theological heresy." The service reminded me of the movement's philosophical origins, in the forties and fifties, in a Catholic sense of alarm at the relativism that was rampant in American life, and an insistence on human frailty. The conservative movement began as a true counterculture; how unlikely that its gloomy creed took hold in America, the optimistic capital of modernity.

Later that day, the Manhattan Institute and National Review Institute held a forum on Buckley's legacy, at the Princeton Club. The panelists - mostly members of the Old Guard - remembered Buckley, traded Latin phrases, and exuded self-satisfaction. Roger Kimball, the co-editor of the dour cultural review The New Criterion, declared that conservatism imposes a philosophical duty on its adherents to enjoy life - to which George Will, not ebullient by disposition, later added, "Politics is fun, because politics involves inherently the celebration of America's first principles... . Politics is an inherently cheerful undertaking, so be of good cheer. That is what Bill left us with." Kimball continued to roll up the score in favor of conservatives. Their reputation for being "un-fun," he said, stems partly from the fact that they are "realists" who are "a wet blanket on people who talk about things like 'The Audacity of Hope' and 'It Takes a Village,' just to pick two terms arbitrarily." The country, he said, "is still suffering from that post-Romantic assault on humanity that is summarized by the term 'the sixties.' This, too, shall pass."

Once the principled levity had died down and it came time for questions, I asked whether the conservative movement was dead. "It would be a sign of maturity if conservatives would stop using the phrase 'conservative movement,' " Will said. "This is now a center-right country, and conservatism is the default position for, I think, a stable Presidential majority." Jay Nordlinger, an editor at National Review, added, "If it's no longer a movement, and really is mainstream, we owe a lot to Bill Buckley and Reagan." But Buckley himself had been more realistic than his eulogists. Sam Tanenhaus, the editor of the Times Book Review and the Week in Review section, who is working on a biography of Buckley, said that in his final years Buckley understood that his movement was cracking up. "He told me, 'The conservative movement lost its raison d'être with the end of Communism and never got it back.' "

Between the Mass and the forum, I had lunch with David Frum. His mood was elegiac and chastened. He now realized that, in 2001, Bush had been right and he had been wrong at their first meeting: the Party did need to change, but not in the way Bush went on to change it. "It wasn't a successful Presidency, and that's a painful thing," Frum said. "And I was a very small, unimportant part of it, but I was a part of it, and that implies responsibility." Frum has made his peace with the fact that smaller government is no longer a basis for conservative dominance. The thesis of his new book, "Comeback: Conservatism That Can Win Again" (Doubleday), whose message Frum has been taking to Republican groups around the country, is that the Party has lost the middle class by ignoring its sense of economic insecurity and continuing to wage campaigns as if the year were 1980, or 1968.

"If Republican politicians quote Reagan, their political operatives study Nixon," Frum writes. "Republicans have been reprising Nixon's 1972 campaign against McGovern for a third of a century. As the excesses of the 1960s have dwindled into history, however, the 1972 campaign has worked less and less well." He adds, "How many more elections can conservatives win by campaigning against Abbie Hoffman and Bobby Seale? Voters want solutions to the problems of today." Polls reveal that Americans favor the Democratic side on nearly every domestic issue, from Social Security and health care to education and the environment. The all-purpose Republican solution of cutting taxes has run its course. Frum writes, "There are things only government can do, and if we conservatives wish to be entrusted with the management of government, we must prove that we care enough about government to manage it well."

This is a candid change of heart from a writer who, in "Dead Right," called Republican efforts to compete with Clinton's universal-health-coverage plan "cowardly." In the new book, Frum asks, "Who agreed that conservatives should defend the dysfunctional American health system from all criticism?" Well - he did! Frum now identifies health care as the chief anxiety of the middle class. But governing well, in conservative terms, doesn't mean spending more money. It means doing what neither Reagan nor Bush did: mastering details, knowing the options, using caution - that is, taking government seriously. The policy ideas in "Comeback" rely on the market more than on the state and are relatively small-bore, such as a government campaign to raise awareness about the dangers of obesity. As with most such books, the diagnosis is more convincing than the cure.

Frum believes that the Republicans need their own equivalent of the centrist Democratic Leadership Council, to make it safe for Republican candidates to tell their interest groups, such as evangelical Christians, what they don't want to hear: that they need to mute their demands if the Party is to regain a majority. At lunch, he said, "The thing I worry about most is if the Republicans lose this election - and if you're a betting man you have to believe they will - there will be a fundamentalist reaction. Not religious - but the beaten party believes it just has to say it louder. Like the Democrats after 1968." He added, "A lot of the problems in the Republican Party will not be fixed."

I asked Frum if the movement still existed. "We'll have people formed by the conservative movement making decisions for the next thirty to forty years," he said. "But will they belong to a self-conscious and cohesive conservative movement? I don't think so. Because their movement did its work. The core task was to stop and reverse, to some degree, the drift of democratic countries after the Second World War toward social democracy. And that was done."

As we started to leave, Frum smiled. "One of Buckley's great gifts was the gift of timing," he said. "To be twenty-five at the beginning and eighty-two at the end! But I'm forty-seven at the end."

When I met David Brooks in Washington, he was even more scathing than Frum. Brooks had moved through every important conservative publication - National Review, the Wall Street Journal editorial page, the Washington Times, the Weekly Standard - "and now I feel estranged," he said. "I just don't feel it's exciting, I don't feel it's true, fundamentally true." In the eighties, when he was a young movement journalist, the attacks on regulation and the Soviet Union seemed "true." Now most conservatives seem incapable of even acknowledging the central issues of our moment: wage stagnation, inequality, health care, global warming. They are stuck in the past, in the dogma of limited government. Perhaps for that reason, Brooks left movement journalism and, in 2003, became a moderately conservative columnist for the Times. "American conservatives had one defeat, in 2006, but it wasn't a big one," he said. "The big defeat is probably coming, and then the thinking will happen. I have not yet seen the major think tanks reorient themselves, and I don't know if they can." He added, "You go to Capitol Hill - Republican senators know they're fucked. They have that sense. But they don't know what to do. There's a hunger for new policy ideas."

The Heritage Foundation Web site currently links to video presentations by Sean Hannity and Laura Ingraham, "challenging Americans to consider, What Would Reagan Do?" Brooks called the conservative think tanks "sclerotic," but much conservative journalism has become just as calcified and ingrown. Last year, writing in The New Republic, Sam Tanenhaus revealed a 1997 memo in which Buckley - who had originally hired Brooks at National Review on the strength of a brilliant undergraduate parody that he had written of Buckley - refused to anoint him as his heir because Brooks, a Jew, is not a "believing Christian." At Commentary, the neoconservative counterpart to National Review, the editorship was bequeathed by Norman Podhoretz, its longtime editor, to his son John, whose crude op-eds for the New York Post didn't measure up to Commentary's intellectual past. A conservative journalist familiar with both publications said that what mattered most at the Christian National Review was doctrinal purity, whereas at the Jewish Commentary it was blood relations: "It's a question of who can you trust, and it comes down to religious fundamentals."

The orthodoxy that accompanies this kind of insularity has had serious consequences: for years, neither National Review nor Commentary was able to admit that the Iraq war was being lost. Lowry, who received the editorship from Buckley before he turned thirty, told me that he particularly regretted a 2005 cover story he'd written with the headline "WE'RE WINNING." He said, "Most of the right was in lockstep with Donald Rumsfeld. We didn't want to admit we were losing and said anyone who said otherwise was a defeatist. One thing I've loved about conservatism is its keen sense of reality, and that was totally lost in 2006." Last year, National Review ran a cover article on global warming, which Lowry, like Brooks, Frum, and other conservatives, listed among the major issues of our time, along with wage stagnation and the breakdown of the family. Although the article, by Jim Manzi, proposed market solutions, the response among some readers, Lowry said, was " 'How dare you?' A bunch of people out there don't want to hear it - they believe it's a hoax. That's the head-in-the-sand response."

A similar battle looms between traditional supply-side tax cutters and younger writers like National Review's Ramesh Ponnuru, who has proposed greatly expanding the child tax credit - using tax policy not to reduce the tax burden across the board, in accord with conservative orthodoxy, but to help families. These challenges to dogma, however tentative, are being led by Republican constituencies that have begun to embrace formerly "Democratic issues." Evangelical churches are concerned about the environment; businesses worry about health care; white working-class voters are angry about income inequality. But nothing focusses the mind like the prospect of electoral disaster: last November, Lowry and Ponnuru co-wrote a cover story with the headline "THE COMING CATACLYSM."

It's probably not an accident that the most compelling account of the crisis was written by two conservatives who are still in their twenties and have made their careers outside movement institutions. Ross Douthat and Reihan Salam, editors at the Atlantic Monthly, are eager to cut loose the dead weight of the Gingrich and Bush years. In their forthcoming book, "Grand New Party: How Republicans Can Win the Working Class and Save the American Dream" (Doubleday), Douthat and Salam are writing about, if not for, what they call "Sam's Club Republicans" - members of the white working class, who are the descendants of Nixon's "northern ethnics and southern Protestants" and the Reagan Democrats of the eighties. In their analysis, America is divided between the working class (defined as those without a college education) and a "mass upper class" of the college educated, who are culturally liberal and increasingly Democratic. The New Deal, the authors acknowledge, provided a sense of security to working-class families; the upheavals of the sixties and afterward broke it down. Their emphasis is on the disintegration of working-class cohesion, which they blame on "crime, contraception, and growing economic inequality." Douthat and Salam are cultural conservatives - Douthat became a Pentecostal and then a Catholic in his teens - but they readily acknowledge the economic forces that contribute to the breakdown of families lacking the "social capital" of a college degree. Their policy proposals are an unorthodox mixture of government interventions (wage subsidies for lower-income workers) and tax reforms (Ponnuru's increased child-credit idea, along with a revision of the tax code in favor of lower-income families). Their ultimate purpose is political: to turn as much of the working class into Sam's Club Republicans as possible. They don't acknowledge the corporate interests that are at least as Republican as Sam's Club shoppers, and that will put up a fight on many counts, potentially tearing the Party apart. Nor are they prepared to accept as large a role for government as required by the deep structural problems they identify. Douthat and Salam are as personally remote from working-class America as any élite liberal; Douthat described their work to me as "a data-driven attempt at political imagination." Still, any Republican politician worried about his party's eroding base and grim prospects should make a careful study of this book.

Frum's call for national-unity conservatism and Douthat and Salam's program for "Sam's Club Republicans" are efforts to shorten the lean years for conservatives, but political ideas don't materialize on command to solve the electoral problems of one party or another. They are generated over time by huge social transformations, on the scale of what took place in the sixties and seventies. "They're not real, they're ideological constructs," Buchanan said, "and you can write columns and things like that, but they don't engage the heart. The heart was engaged by law and order. You reached into people - there was feeling."

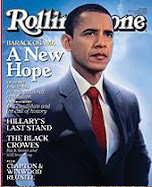

Sam Tanenhaus summed up the 2008 race with a simple formula: Goldwater was to Reagan as McGovern is to Obama. From the ruins of Goldwater's landslide defeat in 1964, conservatives began the march that brought them fully to power sixteen years later. If Obama wins in November, it will have taken liberals thirty-six years. Tanenhaus pointed out how much of Obama's rhetoric about a "new politics" is reminiscent of McGovern's campaign, which was also directed against a bloated, corrupt establishment. In "The Making of the President 1972," Theodore White quotes McGovern saying, "I can present liberal values in a conservative, restrained way... . I see myself as a politician of reconciliation." That was in 1970, before McGovern was defined as the candidate of "amnesty, abortion, and acid," and he defined himself as a rigid moralist more interested in hectoring middle Americans than in inspiring them.

Obama, of course, is an entirely different personality in a different time, but the interminable primary campaign has shown his coalition to look very much like McGovern's: educated, upper-income liberal voters; blacks; and the young. Nixon beat McGovern among the latter even after the Twenty-sixth Amendment lowered the voting age to eighteen; but times have changed so drastically that, according to Pew Research Center surveys, almost sixty per cent of voters under thirty now identify more strongly with the Democrats, doubling the Party's advantage among the young over Republicans since 2004. And the demographic work of John Judis and Ruy Teixeira in their 2002 book, "The Emerging Democratic Majority," showed that the McGovern share of the electorate - minorities and educated professionals working in post-industrial jobs - is expanding far faster than the white working class. This was the original vision of a McGovern adviser named Fred Dutton, whose 1971 book, "Changing Sources of Power: American Politics in the 1970s," cited by Perlstein, foresaw a rising "coalition of conscience and decency" among baby boomers. The new politics was an electoral disaster in 1972, but it may finally triumph in 2008.

If not, it will be because Democrats still can't win the Presidency without the working-class Americans who remain the swing vote and, this year, are up for grabs more than ever. Hillary Clinton has denied Obama a lock on the nomination by securing large majorities of swing voters, beginning in New Hampshire and culminating last week in West Virginia. It took the Obama campaign months to realize that a 2008 version of the McGovern coalition will barely be sufficient to win the nomination, let alone the general election. The question is how Obama can do better with the crucial slice of the electorate that he hasn't been able to capture. Recently, he has gone from bowling in Pennsylvania and drinking Bud in Indiana to talking about his single mother, his wife's working-class roots, and his ardent patriotism on the night of his victory in North Carolina. But the problem can't be solved by symbols or rhetoric: for a forty-six-year-old black man in an expensive suit, with a Harvard law degree and a strange name, to walk into V.F.W. halls and retirement homes and say, "I'm one of you," seems both improbable and disingenuous.

The other extreme - to muse aloud among wealthy contributors, like a political anthropologist, about the values and behavior of the economically squeezed small-town voter - is even more self-defeating. Perhaps Obama's best hope is to play to his strength, which is a cool and eloquent candor, and address the question of liberal élitism as frontally as he spoke about race in Philadelphia two months ago. He would need to say, in effect, "I know I'm not exactly one of you," and then explain why this shouldn't matter - why he would be just as effective a leader for the working and middle class as his predecessors Presidents Roosevelt and Kennedy, who were élites of a different kind. Above all, Obama should absorb what the most thoughtful conservatives already know: that these voters see the economic condition of the country as inextricable from its moral condition.

Last month, I saw John McCain speak in a tiny town, nestled among the Appalachian coal hills of eastern Kentucky, called Inez. He was in the middle of his Time for Action Tour of America's "forgotten places" (including Selma, Alabama; Youngstown, Ohio; and the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans). It was a transparent effort to stay in the media eye and also to say, as his speechwriter Mark Salter later told me, "I'm not going to run an election like the last couple have been run, trying to grind out a narrow win by increasing the turnout of the base. I don't want to run a campaign like that because I don't want to be a President like that. I want to be your President even if you don't vote for me." As every new conservative book points out, the Bush-Rove realignment strategy would fail miserably this year, anyway.

Inez is the place where Lyndon Johnson came to declare war on poverty, in 1964. He sat on the porch of a ramshackle, tin-roof house, which still stands (just barely) on a hillside above Route 3, looking a little like a museum of rural poverty in a county that has recently prospered because of coal. McCain was to appear in the county courthouse, on the short main street of Inez, and the middle-aged men I sat with in the second-floor courtroom all remembered Johnson's visit and had nothing but good things to say about his anti-poverty programs. Kennis Maynard, the county prosecutor, a cheerful, thickset man in a blue suit, had saved enough money for law school from a job in the mines that he got with the help of a federal work program. His family was so poor that they were happy to accept government handouts of pork, canned beans, and cheese. The courthouse in which we were sitting was a New Deal project, circa 1938. Maynard, like the other men, like most of nearly all-white Martin County, is Republican - mainly, he said, because of cultural issues like abortion. But Maynard and the others said that McCain had better talk about jobs and gas prices if he wanted to keep his audience.

John Preston, who is the county's circuit-court judge and also its amateur historian, Harvard-educated, with a flag pin on his lapel, said, "Obama is considered an élitist." He added, "There's a racial component, obviously, to it. Thousands of people won't publicly say it, but they won't vote for a black man - on both sides, Democrat and Republican. It won't show up in the polls, because they won't admit it. The elephant's in the room, but nobody will say it. Sad to say it, but it's true." Later, I spoke with half a dozen men eating lunch at the Pigeon Roost Dairy Bar outside town, and none of them had any trouble saying it. They announced their refusal to vote for a black man, without hesitation or apology. "He's a Muslim, isn't he?" an aging mine electrician asked. "I won't vote for a colored man. He'll put too many coloreds in jobs. Colored are O.K. - they've done well, good for them, look where they came from. But radical coloreds, no - like that Farrakhan, or that senator from New York, Rangel. There'd be riots in the streets, like the sixties." No speech, on race or élitism or anything else, would move them. Here was one part of the white working class - maybe not representative, but at least significant - and in an Obama-McCain race they would never be the swing vote. It is a brutal fact, and Obama probably shouldn't even mention it.

McCain appeared to a warm reception. I had seen him in New Hampshire, where he gave off-the-cuff remarks with vigor; when he is stuck with a script, however, he is a terrible campaigner. Looking pallid, he sounded flat, and stumbled over his lines - and yet they were effective lines, ones that Obama would do well to study. "I can't claim we come from the same background," McCain began. "I'm not the son of a coal miner. I wasn't raised by a family that made its living from the land or toiled in a mill or worked in the local schools or health clinic. I was raised in the United States Navy, and, after my own naval career, I became a politician. My work isn't as hard as yours - it isn't nearly as hard as yours. I had an easier start." He paused and went on, "But you are my compatriots, my fellow-Americans, and that kinship means more to me than almost any other association."

McCain mentioned Johnson's visit and the war on poverty, expressing admiration for its good intentions but rebuking its reliance on government to create jobs - rebuking it gently, without the contempt that Reagan would have used. He called for job-training partnerships between business and community colleges, tax deductions for companies bringing telecommunications to rural areas. It was a moderate, reform-minded Republicanism. He didn't use any of the red-meat language that made two generations of white voters switch parties.

"McCain is not a theme guy," David Brooks said. "He reacts - he has moral instinct, which I think is quite a good one." Other conservatives complained to me that he has no ideology at all. "Let's face it," Brooks said. "What McCain's going to do is say, 'I'm not George Bush. I'm not like the Republican Party you knew.' " Most Presidential candidates move to the center once they've locked up the nomination; McCain, however, still has to try to win over the suspicious Republican right, and he recently vowed to appoint only judges who "strictly interpret" the Constitution to the bench. But pledges of fealty to his party's ideological interest groups diminish what's appealing about McCain. "Feeling fraudulent is very debilitating to him," Mark Salter said.

When McCain opened the floor for questions, a woman asked about border security. He replied, to general laughter, "This meeting is adjourned." Another woman asked him to discuss his religious faith, and McCain told a story from his imprisonment, about a generous gesture by a North Vietnamese guard one Christmas Day. I'd heard him tell the same story in New Hampshire; it seemed to be his stock answer, and he hurried through it. Other questions came, about gas prices and jobs going overseas and foreclosures and education costs, and McCain's answers - a summer federal-gas-tax holiday, a cut in the capital-gains tax, charter schools, federal home loans, job-training programs - didn't seem to move either him or his audience very much.

Members of the audience began to appeal to McCain with the old polarizing language, but he refused to take the bait. A state senator asked what he thought about Obama's recent comments on rural voters, religion, and guns. McCain turned the question around. "Let me ask you: Do you think those remarks reflect the views of constituents?"

"I think they reflect the views of someone who doesn't understand this neck of the woods," the state senator replied, to the biggest ovation of the day.

"Yes, those were élitist remarks, to say the least," McCain said quickly, walking away.

Judge Preston had a question. McCain had mentioned Clinton's vote for a million-dollar earmark for a museum in Woodstock, New York. Had he attended the concert? It was an obvious setup for a standard McCain joke, and he seemed positively embarrassed by it. "I'll give my not-so-respectful answer," he said. "I was tied up at the time."

It was a remarkably subdued performance. McCain doesn't try to stir a crowd's darker passions or its higher aspirations. He doesn't present himself as a conservative leader; he is simply a leader. His favorite book, according to Salter, is "For Whom the Bell Tolls," because it's the story of a man who struggles nobly even though he knows the effort is doomed. McCain says to audiences, Here I am, a man in full, take me or leave me. This might be the only kind of Republican who could win in 2008.

http://www.blogger.com/post-create.g?blogID=4233217762125074861